Here are 46 more pages.

The most interesting thing is the Change of Venue motion. I don't recall if Bug mentions that in his novel or not....

Google books seems to say that he doesn't but the search function is behaving oddly.

Anyway....

A change of venue means that Charlie asked that the trial be moved out of Los Angeles. He felt there was too much publicity because of the murders in LA and maybe he could get a fair trial on the moon or somewhere.

Fact is I am not sure he could have gotten a fair trial anywhere based on the publicity, but then the facts show that he never tried to get one either.

The motion was shot down.

...Truth has not special time of its own. Its hour is now — always and indeed then most truly when it seems unsuitable to actual circumstances. (Albert Schweitzer).....the truth about these murders has not been uncovered, but we believe the time for the truth is now. Join us, won't you?

Wednesday, September 24, 2014

Tuesday, September 23, 2014

Sharing the Yalkowsky Collection 2014 #2

Here is the next 98 pages.

Lots of legal motions and shits, plenty to discuss if someone wants to ask questions, or we can stop this whole thing right here.

I mean, there's naked photos of Kitty to oogle so what are we doing here right?

Lots of legal motions and shits, plenty to discuss if someone wants to ask questions, or we can stop this whole thing right here.

I mean, there's naked photos of Kitty to oogle so what are we doing here right?

What Shall We Ask?

We are thrilled to be sharing Patricia Krenwinkel's story with you,

and will begin shipping pre-orders next week!

As we continue with media buzz and sold-out festival screenings, it's incredible to experience how audiences are responding to Patricia's story. As the film continues to win festival awards and have sold-out screenings, we cannot wait to hear about your reactions to the film. Soon we'll have a way for you to send a message to Patricia through our website, so make sure to check our website once you've had a chance to watch the film. Stay tuned for even more exciting news, and thanks again for your recent purchase of Life After Manson.

Monday, September 22, 2014

Sharing the Yalkowsky Collection 2014 #1

You can search the blog going back eight fucking years to learn about the Yalkowsky Collection. Suffice it to say it involved me spending a lot of money and getting a shitload of milk crates filled with legal documents. Fine...

Then we used interns and little muchkins to transcribe some of the documents. Then that got boring and everything got stuck in storage.

The best thing that happened was that the collection included a copy of THE VINCENT T. BUGLIOSI STORY which revealed clearly that BUG stalked his milkman before the TLB case and beat his mistress after it. The Col made copies and now every scholar has access to it.

Storage costs money, much like Matt's pizza costs money and so the Col had the collection scanned and then chucked.

Beginning today we will provide all true scholars with the collection. Here's 89 pages of it. It is mostly first hand documents (Charlie's pro per stuff is the best) from the early days of the case.

If there is something you would like this disbarred attorney to discuss in a post you can mention it in the comments.

I hope this works and is received well since , well, you know, it cost money and shit.

Then we used interns and little muchkins to transcribe some of the documents. Then that got boring and everything got stuck in storage.

The best thing that happened was that the collection included a copy of THE VINCENT T. BUGLIOSI STORY which revealed clearly that BUG stalked his milkman before the TLB case and beat his mistress after it. The Col made copies and now every scholar has access to it.

Storage costs money, much like Matt's pizza costs money and so the Col had the collection scanned and then chucked.

Beginning today we will provide all true scholars with the collection. Here's 89 pages of it. It is mostly first hand documents (Charlie's pro per stuff is the best) from the early days of the case.

If there is something you would like this disbarred attorney to discuss in a post you can mention it in the comments.

I hope this works and is received well since , well, you know, it cost money and shit.

Wednesday, September 17, 2014

The Tapes Go Round and Round

Like we like to do at the ONLY Official Tate LaBianca Murders Blog on the web whenever there is ANY serious news at all we like to discuss it. Not in a Mansonblog "Where are they now " kind of way or even in a LSB Special needs kind of way but in a Dragnet "Just the facts ma'am" kind of way.

So let's discuss yesterday's post by the reclusive Tom O'Neill.

The Col knew Tom was working on this article for several weeks but promised not to discuss it. And then of course Tom has been working on his book (mysteriously called a "Project" in the article, repeatedly) since I last saw him and that was 2001. So I didn't know if he would actually release this.

--> The biggest thing seems to be that the LAPD went to a lot of trouble to get these tapes, Tom helped them, and now they won't let him hear them.

That kind of sucks.

This leads to the question of what can be on these tapes.

Maybe more victims? Maybe more motive? Maybe nothing?

But Watson did try to block their release. Lawyers cost money and shit. And the LAPD is in fact not letting anyone hear them.

--> Of course if Tex admits killing Marina Habe that isn't evidence and it may not be true.

--> If Tex says that Leslie actually stayed in the car at Waverly THAT isn't evidence and it won't get her out.

The Col had a brief exchange with Tom this am. As a defrocked minister and disbarred attorney the Col is a bit slow and was wondering what could possibly be on the tapes that would be so shocking.

--> Apparently maybe Tex exposes The BUG as a liar and a fraud.

But that was exposed years ago to ANY real researcher and certainly blown open to Internet Students when the Col released THE VINCENT T. BUGLIOSI STORY to key personnel back in 2006.

So I ask you, Tex, the baby killer, the pregnant lady stabber, who would believe anything the fucker says?

Yet the LAPD does in fact seem to not be releasing the tapes and the press seems to be not reporting it.

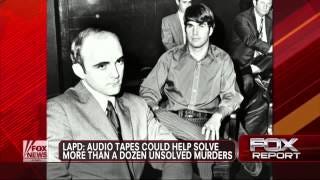

Now remember (see image) Tom is also the guy who showed up on some shitty Cable show YEARS ago talking about Charlie's ranch-based Kung Fu Classes. I've also had people like Statman and Nancy Pitman write to me over the years describing how, shall we say, he AGGRESSIVELY pursued his agenda, much to the dismay of people including Paul Tate and his last lady. So where Tom is concerned an open mind is needed.

But leaving aside him being butthurt over the embargo, how about HISTORY???? There are no open homicide investigations REALLY that LAPD is exploring. Buster the cadaver dog is a joke, still looking for the Black Dahlia over on Franklin a year ago. There is no reason to not release the tapes to Tom and scholars.

But then there is no reason to have a meeting with Orca Tate about releasing Bruce Davis (not convicted of killing anyone Orca ever met or had plankton with) and LAPD did that.

Kind of a weird story. I'll be following it.

So let's discuss yesterday's post by the reclusive Tom O'Neill.

The Col knew Tom was working on this article for several weeks but promised not to discuss it. And then of course Tom has been working on his book (mysteriously called a "Project" in the article, repeatedly) since I last saw him and that was 2001. So I didn't know if he would actually release this.

--> The biggest thing seems to be that the LAPD went to a lot of trouble to get these tapes, Tom helped them, and now they won't let him hear them.

That kind of sucks.

This leads to the question of what can be on these tapes.

Maybe more victims? Maybe more motive? Maybe nothing?

But Watson did try to block their release. Lawyers cost money and shit. And the LAPD is in fact not letting anyone hear them.

--> Of course if Tex admits killing Marina Habe that isn't evidence and it may not be true.

--> If Tex says that Leslie actually stayed in the car at Waverly THAT isn't evidence and it won't get her out.

The Col had a brief exchange with Tom this am. As a defrocked minister and disbarred attorney the Col is a bit slow and was wondering what could possibly be on the tapes that would be so shocking.

--> Apparently maybe Tex exposes The BUG as a liar and a fraud.

But that was exposed years ago to ANY real researcher and certainly blown open to Internet Students when the Col released THE VINCENT T. BUGLIOSI STORY to key personnel back in 2006.

So I ask you, Tex, the baby killer, the pregnant lady stabber, who would believe anything the fucker says?

Yet the LAPD does in fact seem to not be releasing the tapes and the press seems to be not reporting it.

Now remember (see image) Tom is also the guy who showed up on some shitty Cable show YEARS ago talking about Charlie's ranch-based Kung Fu Classes. I've also had people like Statman and Nancy Pitman write to me over the years describing how, shall we say, he AGGRESSIVELY pursued his agenda, much to the dismay of people including Paul Tate and his last lady. So where Tom is concerned an open mind is needed.

But leaving aside him being butthurt over the embargo, how about HISTORY???? There are no open homicide investigations REALLY that LAPD is exploring. Buster the cadaver dog is a joke, still looking for the Black Dahlia over on Franklin a year ago. There is no reason to not release the tapes to Tom and scholars.

But then there is no reason to have a meeting with Orca Tate about releasing Bruce Davis (not convicted of killing anyone Orca ever met or had plankton with) and LAPD did that.

Kind of a weird story. I'll be following it.

Tuesday, September 16, 2014

Our Frenemy Tom is Pissed at LAPD

The Tale of the

Manson Tapes

Why doesn’t Los Angeles law enforcement want to reveal what’s on the 45-year-old Tex Watson tapes — and why isn’t the press reporting it?

By Tom O'Neill

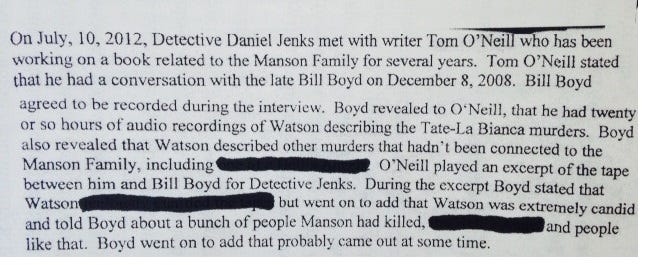

Last year, on April 12, two Los Angeles Police Department detectives were about to board a plane at Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport with 44-year-old tape recordings of an infamous murderer describing his crimes to his attorney. Moments before they boarded the craft, one of the detective’s cell phones rang. “Are you on the plane yet?” Los Angeles county deputy district attorney Patrick Sequeira asked Detective Dan Jenks, LAPD Unsolved Homicides. “Don’t jinx it!” Jenks replied. Charles “Tex” Watson The tapes of convicted Manson Family murderer Charles “Tex” Watson, detailing the horrific killings he and several female accomplices had carried out on the orders of their cult leader, Charles Milles Manson, over two hot nights in August 1969, had been at the center of a court battle that went all the way to the Federal Court of Eastern Texas the preceding year. Fifteen days earlier, U.S. District Judge Richard A. Schell had affirmed a bankruptcy court judge’s ruling that, despite being recordings of a defendant describing his crimes to his attorney, the tapes were no longer protected by attorney-client privilege because the defendant and the attorney had later shared the tapes with an author who co-wrote a memoir with the imprisoned Watson that was published in 1978. Because of a miscommunication DDA Sequeira told me he’d discovered, Watson’s attorneys had been informed that they had thirty days to appeal Judge Schell’s ruling, when, in fact, they only had fourteen. When he learned of the error, Sequeira later told me, he told Jenks and his partner to be in Texas on the fifteenth day to take possession of the tapes — before Watson could discover the error and file an appeal on time (hence the jittery nerves of the Los Angeles law enforcement officials). But they procured the tapes and had them back at LAPD headquarters — secured in a safe purchased

especially for them — that same evening. Sequeira, who represented the state at all Manson Family member parole hearings from 2006 until last March, called me four days later to report the success of their secret mission. “Without you we wouldn’t have these tapes, let alone known they existed,” he said. “We owe you big time.” He would do his best to make sure I got in to hear them, he promised, ending one of the last conversations we would ever have. Watson and attorney Bill Boyd, Dallas, Texas, 1970 In November 1969, after being taken into custody near his hometown of Copeville, Texas, for questioning in the unsolved Tate-LaBianca murders that had occurred three months earlier, Watson was asked by his defense attorney, Bill Boyd, to describe his crimes with the Manson Family on tape. I learned about the tapes’ existence during an interview with Boyd in December of 2008. The 23-year-old former high school star athlete spared no “details,” Boyd told me in our taped phone call, describing how he and his accomplice, Susan Atkins (then 21), stabbed pregnant actress Sharon Tate to death as she begged for the life of her unborn baby. In addition to the “candid” and “very open” account of the murders of Tate and four visitors to her estate that evening (who were stabbed a total of 102 times and killed on the orders of Manson to ignite an apocalyptic race war he called “Helter Skelter”), Watson also recounted the equally gruesome murders of grocery store chain magnate Leno LaBianca and his wife, Rosemary, the following night. (Stabbed a total of 67 times, the killers left a knife and fork protruding from Leno’s corpse, carved the word “WAR” in his stomach, and, as they had the night before, scrawled phrases like “DEATH TO PIGS” and “HEALTER SKELTER” [sic] in the victims’ blood on surfaces of their home.) Tate House Victims: Voytek Frykowski, 32; Sharon Tate, 26; Steven Earl Parent, 18; Jay Sebring, 35; Abigail Folger, 25 (AP Photo) Leno and Rosemary LaBianca, 44 and 38, killed the next night in Los Feliz Boyd volunteered that Watson also described “other” murders committed by the Family that had never been discovered or connected to them by the authorities. Watson’s twenty-hour taped confession was the first recorded description of what would rank among history’s most horrific and baffling crime sprees. (The victims were strangers to their killers. At the trial, the prosecution would argue that Watson and his three accomplices — Atkins, a

San Jose, California native, who sang in her high school glee club; Leslie Van Houten, 19, a homecoming princess from Monrovia, California; and Patricia Krenwinkel, 21, a one-time Catechism teacher from Los Angeles — had been brainwashed by their “guru,” Manson, 34, an ex-con from Cincinnati who’d convinced them he was Jesus Christ and the Devil.) Atkins, Krenwinkel and Van Houten shortly after carving “x”s into their foreheads (mimicing Manson), on their way to trial at the Los Angeles Hall of Justice Written on the wall of the LaBianca home in the victims’ blood I wanted to listen to the tapes, not just because they allegedly contained information about unsolved murders committed by the group, but also because they constituted the earliest known narrative of how and why these killings occurred. In my (by then) nine-year investigation of the case for a project I was working on, I’d uncovered a significant amount of documentary evidence suggesting that the crimes — and the reasons behind them — were different than the official narrative presented by prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi at trial and in his best selling book about the case, Helter Skelter. But Boyd retreated from his original offer to let me listen to the tapes once it dawned on him how egregiously he had violated his client’s confidentiality. Less than a year later, he was dead of a sudden heart attack. Several years after that I began a lengthy crusade to get the tapes, first from his family and later from a court-appointed trustee who took possession of them after Boyd’s law firm went bankrupt. In March of 2012, I finally convinced the trustee that the tapes hadn’t been protected by attorney-client privilege for some time because in 1976 Watson had shared them — or a portion of them — with the co-author of his book, Will You Die For Me? The Man Who Killed for Charles Manson Tells His Story. (Watson’s death sentence was commuted to life in prison in 1972 when the California Supreme Court ruled the death penalty unconstitutional.) But because I’d also persuaded the trustee, Linda Payne, that it was possible the tapes contained evidence of unsolved murders — murders that weren’t disclosed in his memoir — she decided to release them to Los Angeles law enforcement instead. Upon learning of Payne’s plan to turn over the tapes to the LAPD, Watson — who insisted he knew of no other murders beside the nine the Family had been convicted of — waged a year-long battle in the Texas courts to prevent the tapes’ release. But he had a formidable foe in the LAPD. So determined was the LAPD to get the tapes that when it appeared that the case might be stalled in the courts, they took the unprecedented action of attempting to bypass the court’s authority by seeking a search warrant for their release. In the summer of 2012, I was summoned to LAPD headquarters, where officials listened to my complete taped interview of Boyd (to ensure his comments about “other” murders committed by the Family hadn’t been distorted or taken out of context) and used it as the basis of their warrant. When it was finally executed at Payne’s office in October 2012 by detectives from Los Angeles and the Fort Worth Police department, she called her own attorney, who immediately contacted Judge Schell. Schell issued an emergency order blocking the warrant and made sure to rebuke the officers in his written decision for attempting to circumvent his authority. (“The LAPD has provided no explanation as to why this court should shortcut the usual procedure for determining a bankruptcy appeal given that the investigation the LAPD wishes to reopen involves murders that occurred 42 years ago,” he wrote). From the warrant Regardless of his feelings about the LAPD, Schell ultimately ruled in the department’s favor, affirming a court decision from a year earlier that the tapes were no longer protected by attorney-client privilege and should be released. Fourteen business days later, according to Sequeira, on April 11, 2013, LAPD detectives returned for a second time to Payne’s office, but this time left with the tapes. But everything the LAPD has done since retrieving the tapes has raised questions that, while there might not be information about other, unsolved murders on them — the reason they were so assiduously sought in the first place — there may be something else on them, something far more significant, though damaging to the nearly half century-closed case. That question seems all the more relevant in light of a recent disclosure by two members of the murder victims’ families who had a secret meeting with two of the only three people who’ve likely heard the tapes — DDA Sequeira and Det. Jenks, the officer assigned to supervise the investigation (the third person is an unnamed homicide detective who transcribed the tapes). The startling information shared at that meeting may provide something of an explanation for the peculiar behavior of Sequeira and the LAPD since receiving the tapes. (Det. Jenks, former DDA Sequeira and the Los Angeles Police Department did not respond to multiple requests for comment by a Medium fact checker; at press time, the Los Angeles District Attorney’s office would only confirm that Sequeira had communicated with me about the tapes). Patrick Sequeira speaks to the press after Leslie Van Houten’s 2006 parole hearing In April 2013, when Sequeira excitedly called me to share the news that they had finally obtained the tapes, he was 60 and had spent the previous seven years representing the District Attorney’s office at all of the Manson Family members’ parole hearings. Shortly after taking over the job from Stephen Kay — the near-legendary DDA who’d successfully kept the five convicted Tate-LaBianca killers (Manson, Watson, Atkins, Krenwinkel, and Van Houten) behind bars for 35 years — Sequeira, like Kay, became a source for my project about the Manson Family. We frequently spoke and shared information about the case. Sometimes I even provided trial transcripts and old police reports he needed for parole hearings. I also put him in touch with the families of two lesser-known Manson murder victims — Gary Hinman, killed a week before Tate-LaBianca, and Donald “Shorty” Shea, killed two weeks after — when he needed them to appear at hearings for a sixth Manson Family member, Bruce Davis (who also killed on Manson’s orders, but didn’t participate in Tate-LaBianca). And, as my efforts to wrest the tapes from Payne escalated to the point where she decided to release them, she surprised both me, and Sequeira (who hadn’t been involved in the process), by contacting his office and offering them the tapes. Sequeira was open with me about how much they owed their possession of the tapes to my efforts. He said in that first conversation after receiving them that he wanted me to come in and listen to them with his colleagues to help decipher their content. “You know more about this stuff than anyone here,” he told me. The deputy was clearly excited at the prospect of opening new murder cases against one of the most notorious killing groups in California history. And, like Stephen Kay before him, he had become almost evangelically committed to keeping the Manson Family members behind bars for their remaining years on the planet. Certainly there would be information on the tapes — even if it wasn’t information about other murders — that would be useful in his increasingly difficult arguments against the parole of several Family members (particularly the now grayed and grandmotherly Leslie Van

Houten and Patrica Krenwinkel, both of whom renounced Manson in their earliest years of incarceration and have been model prisoners ever since). As in all our conversations since the news of the tapes’ existence went public a year earlier and the court battle began, Sequeira demanded I keep quiet about the latest development. He should’ve known he didn’t have to. Van Houten, 64, at her 20th parole hearing, June 5, 2013 Krenwinkel, 66, at her 13th parole hearing, Jan. 20, 2011 (Reed Saxon / AP) Since the story broke in May 2012 that the LAPD was seeking the tapes, I had refused to speak to the few reporters who’d learned I was the one who originally unearthed them. When the first stories appeared in the press quoting LAPD Chief Charlie Beck’s letter to Payne requesting the tapes — because, he wrote, “The LAPD has information that Mr. Watson discussed additional unsolved murders committed by the followers of Charles Manson” — I was surprised the reporters didn’t try to ferret out the source of Chief Beck’ s “information.” But I was pleased that the first one to discover it, NBC4 Los Angeles news reporter Patrick Healy (who originally broke the story of the LAPD’s interest in the tapes), honored my request to be omitted from his coverage in exchange for a possible future interview. The implicit understanding I had with Sequeira and Jenks from the outset was that if I kept silent about my knowledge of the tapes and their content — Watson’s attorney Boyd had shared specific details of two unsolved murders with me that the LAPD didn’t want publicized — I would eventually be granted access. But Sequeira was unusually worried that the LAPD’s possession of the tapes would leak. He was sure, he said, that if Watson learned they had them he’d try to get a court order forcing their return. I didn’t state the obvious: Watson had missed his deadline to appeal so the LAPD rightfully had them and was copying them as we spoke. If he somehow got a court order, they could send the originals and keep their copies. They’d still have the information they needed to pursue their cases. Instead, I assured him that I would continue to keep my counsel. A week later, on April 23, 2013, we spoke again, but this time he sounded guarded, much less effusive than usual. They were still copying the tapes, he said, and a detective from Unsolveds was simultaneously listening to them and taking notes. They hadn’t told him anything about what was or wasn’t on them, he added, and he didn’t think he’d get to hear them until the LAPD’s review was complete. He’d reminded Jenks that I should be brought in to help out, but Jenks was reluctant. They’d been “burned” by the press in similar situations before — he made a reference to the Robert Blake murder case — and Jenks didn’t want to take any chances. As if to reassure me that the strict precautionary measures weren’t limited to me (and, evidently, to him), he confided that he hadn’t even told his own boss — the DA — or his staff that they had the tapes. Two days later, Sequeira called me at 9:40 p.m. as he was driving to a ski vacation in Mammoth, California. He’d heard that Watson had filed an appeal for the tapes the day before — the last day of the thirty-day deadline — and wanted to know what I knew about it. I hadn’t heard anything, I said, but assured him it made no difference: They had the tapes and were reviewing them, and the time for the appeal had lapsed (it wasn’t thirty days, as Sequeira knew, it was fourteen — that’s why they had them). But he was worried, repeating his fear that Watson would try to get them through a court order. Though he still claimed not to know what was on them, I was beginning to have my suspicions. I waited until after Sequeira’s scheduled return from his week-long vacation before calling him again, on May 7. He hadn’t spoken to anyone yet, he said in a hurried voice, but planned to call Jenks that afternoon. He had another call he had to take, he added, but would let me know as soon as he learned anything. On May 9, I sent an email instead of calling him. “Can you throw me a bone?” I asked. It’d been four weeks since the LAPD got the tapes, I reminded him — certainly they’d shared something with him by now. He didn’t have to give me any specifics, just let me know if all the effort and waiting had been worth it. He replied that they hadn’t told him anything, and he hoped to know something the following week. I couldn’t help myself: “That’s pretty stunning information,” I wrote back. “You dispatch them to retrieve the tapes, speak to them while they’re in Texas in the process of getting them from Linda Payne and now, a month later, they still haven’t told you what’s on them?” I suspected Sequeira had played loose with the facts with me once before and I suspected he was doing it again. After I’d gone to LAPD headquarters the previous July to play the tape of the Boyd interview for the warrant he and Jenks were preparing, they’d executed it on October 3, 2012, without telling me. That was okay; it wasn’t my business to know. But when I asked Sequeira in an October 12, 2012, phone conversation when they were going to go to Texas with the warrant, he told me they’d changed their plans: They’d decided to request an ex parte meeting with Judge Schell and see if they could persuade him to release the tapes rather than try to get them with a warrant. A week after that conversation, the Associated Press broke the story that the warrant had been executed and blocked on October 5, 2012. Had Sequeira lied when he told me they’d changed their plans? They’d already done the warrant when we spoke, and it had been blocked by the judge. Since it hadn’t been discovered by the press, had he decided he could keep it from me? We didn’t speak for half a year after that. When we did, he claimed that the LAPD hadn’t told him about their failed effort until after he’d spoken to me. That, like the things he was telling me now, didn’t add up. He ignored the email but nine days later, on May 18, answered his cell when I called him at home on a Saturday. The verdict was in: There was nothing about unsolved murders or other murders by the Family on the tapes, he told me. The information had been relayed to him by Jenks, and he still hadn’t listened to them himself. “I don’t even know if they’ll let me listen to them,” he added. When I asked if there was anything on the tapes that diverged from the historical narrative of the crimes and how they occurred — information he might be able to use to impeach Family members at their parole hearings — he said no. Watson had told the same story he’d told at his trial, in his book, and at all his parole hearings, he said, and there was no new information. But what happened next shifted the balance in our relationship, and though I wasn’t aware of it then, ended it once and for all. I told him that the time had come for me to write a piece about the tapes for publication. The press still didn’t even know the cops had the tapes. I had an exclusive — in addition to the inside story of the battle for the tapes — and since there was nothing of value on the tapes to law enforcement or the parole board, there was no longer any reason to keep quiet. He exploded.

“Don’t do that! If Watson finds out we have them he’ll try to get a court order to get them back.” But what difference did it make? I replied. There was nothing on them. Then I shared something with him he didn’t know yet. After he called me expressing worry about Watson’s appeal three weeks earlier, I emailed the trustee who’d had the tapes to see if Watson’s attorneys had been notified that they’d been transferred to the LAPD. They had, she responded. So Watson knew, I told Sequeira, for at least two weeks, possibly longer — but that didn’t deter Sequeira in the least. I should wait until his office got a copy of the tapes, he said. That way if Watson sued for them he’d have to sue both the police department and the district attorney’s office for the tapes. The LAPD would never fight the suit, he said, “but we would.” Nothing he was saying made sense. He’d just said he didn’t know if he’d ever get to hear the tapes; now he was telling me I should wait until he got his copy? And, again, what difference did it make if there was nothing that could be used in either a criminal investigation of other murders or at parole hearings? Nonetheless, I decided to acquiesce to his demands. I couldn’t preclude the possibility that there was, in fact, a murder investigation underway that he couldn’t tell me about. I also wanted to hang on to the shred of a chance I still had to listen to them. To alienate him now would eliminate that possibility forever. But when I said I’d at least begin the lengthy process of filing a California Public Records Act request with the Discovery Section of the LAPD to listen to the tapes, he erupted again. The request would alert the media to the fact they had the tapes. Again, I said, so what? There’s nothing on them. He still had no answer, just the implicit threat that if I did anything that resulted in the press — not Watson now, because Watson knew — learning that the LAPD had the tapes, I’d never get to hear them. “Just be patient, Tom,” he pleaded. Though it made no sense, I promised to continue to be silent. It was the last conversation we ever had. So it was hardly a surprise when, five days later, the LAPD provided a different narrative to the press when it was finally reported that they had the tapes. The Associated Press broke the story — “Manson Disciple’s Tapes Being Analyzed by LAPD,” ran their May 23, 2013, headline. Beneath it: “Detective David Holmes said the department has had the tapes for a couple of weeks and Robbery Homicide and the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office are analyzing them.” The next day’s Los Angeles Times followed up, reporting: “LAPD Cmdr. Andrew Smith said the department’s elite Robbery Homicide Division, along with Los Angeles County prosecutors, are starting to review…tapes of conversations between one of Charles Manson’s most fervent followers and his late attorney to see whether it can help solve more cases from that period.” Then the papers and the TV news outlets stopped covering the story. More than a year has passed since the May 23, 2013, AP report that the LAPD had the tapes for “a couple of weeks” and — with the DA office’s assistance — were “starting” to analyze them. Except for the stories around the globe repeating the AP’s scoop in the 24 hours following it, not a single additional story has appeared in the mainstream media about the tapes. Locally, NBC News4 Los Angeles filed a dozen stories on the Texas court battles between May 24, 2012 and May 24, 2013; the Los Angeles Times ran five stories between May 24, 2012 and May 25, 2013 (one on the front page) and hosted an online discussion of the blocked search warrant moderated by its city editor and chief crime reporter, Richard Winton. Yet neither of them — nor any of the local outlets that so feverishly covered every development in the court battle for the tapes — has published or broadcast a follow-up story on what might or might not be on them. By the autumn of 2013, months after Sequeira had stopped returning my calls and emails, I contacted five local

reporters who’d covered the LAPD’s efforts to get the tapes and asked them why they hadn’t done any follow-up reporting. They all told me the same thing: While their LAPD sources told them off the record that there was no information about other murders on the tapes, no one at the department would go on the record with the same statement. They all seemed to agree that that, in and of itself, was a story, but none of them would report it. Further, two of the reporters — the AP’s Tami Abdollah and the Los Angeles Times’ Richard Winton — told me they filed California Public Records Act requests for the tapes to the LAPD, but were denied. Winton’s denial, he said, cited Government Code Section 6254 (f), which contends that the tapes are exempt from disclosure because they were part of an “ongoing investigation.” Winton, a Pulitzer Prize-winning crime reporter, called the response “strange” and the behavior of the cops “cagey,” asking what could they be investigating “since 1969,” if not unsolved murders? (There is no statute of limitations on murder in the U.S.) And, despite the fact that the response appears to directly contradict the LAPD’s off the record claim that there is no information about “other” murders on the tapes (the A.P.’s Linda Deutsch emailed me that her LAPD “sources” told her off the record, “they had gone through them carefully and found nothing in them to be pursued”), Winton, Abdollah, Deutsch and their colleagues in the Los Angeles press corps evidently don’t believe that contradiction — and the fact that the LAPD refuses to release new information about a 45-year-old closed case — was worth reporting. The LAPD embargo on the tape story isn’t limited to the local press. In November, Erik Hedegaard, a reporter for Rolling Stone, called me as he was preparing to publish a story on Charles Manson that he’d been working on for more than a year. Though, he wasn’t covering the tapes angle — his piece focused mostly on Manson’s life behind bars today — he agreed to call the LAPD and try to get an on-the-record comment about them. His three calls weren’t returned, Hedegaard later told me, adding that he finally gave up after the issue had gone to press. Since April, Benett Kessler, a reporter who’s been covering the Manson Family for the last five years in Inyo County, California (where the Family was apprehended for the last time at their desert hideout in October 1969), has been trying to get a comment on the tapes from the LAPD for a story she was preparing for the online outlet Sierra Wave. Despite several promises that a comment was forthcoming, none ever came. When I checked in May, Kessler told me that the LAPD had stopped returning her calls and emails. A possible explanation for the LAPD’s refusal to comment on the tapes and Deputy DA Sequeira’s confusing exchanges with me about them materialized this past spring, when two family members of the Tate victims had a secret meeting with Sequeira and Jenks at LAPD headquarters. Debra Tate, the younger sister of Sharon Tate, and Anthony DiMaria, the nephew of hair stylist Jay Sebring (who was murdered alongside Tate), are the highest profile members of the victims’ relatives, and both attend every parole hearing to advocate against the release of their loved ones’ killers. They also have long believed, like prosecutors Bugliosi and Kay, that the Family had committed other murders that had never been connected to them. Jenks and especially Sequeira were at least morally obligated, at some point, to sit down with Tate and DiMaria and tell them what they learned from the tapes. In light of what happened afterward, both officials now probably wish they hadn’t. There were no other murders described by Watson, Tate and DiMaria were informed at the meeting. And there wasn’t even anything they could use against Family members at their parole hearings. There was nothing new on the tapes or nothing that diverged from the story Watson had always stuck to. But when they asked to listen to the tapes, or at least be allowed to read their transcripts, the officials recoiled. They wouldn’t be able to do that, Tate and DiMaria were told, because if they did it would set a precedent forcing them to have to release the tapes to the public, which they had no intention of doing. When Tate and DiMaria asked what difference that would make if there was nothing of value on them, the cop and deputy DA said they didn’t want the tapes exploited by the media. But that wasn’t a good enough answer, especially for Tate, who mentioned filing a Public Records Act request for them. It was about then, she later told me, that Jenks and Sequeira dropped their bombshell. There was, in fact, something new on the tapes, they were told, something that might “jeopardize” the convictions of several Family members. They clearly didn’t want to say anymore, but when pressed, according to Tate, they finally conceded that Watson “minimized the involvement” of the women in the murders — presumably, Atkins (who died in prison in 2009), and Krenwinkel and Van Houten, who are serving life terms. They suggested, Tate told me, that Watson’s first account to Boyd contradicted his later courtroom and parole hearing testimony (as well as his book), but nonetheless was compelling enough to challenge the historic narrative of the crime presented by prosecutor Bugliosi at trial and in his book. Tate, who I consider a friend as well as long-time source, originally decided not to share this information with me because she was worried that it might cause the release of women she’s personally fought for decades to keep behind bars. But she was troubled enough by its ramifications that she later changed her mind. (DiMaria, while originally confirming Tate’s account of the meeting, later backpedaled, stating in an email: “I was told at the meeting that there was no new information on the tapes. I was convinced this to be true. And continue to believe so today.”) Debra Tate testifies at Susan Atkins’ last parole hearing in September, 2009, twenty-two days before her death from cancer. AP reporter Linda Deutsch looks on Whatever the new information on the tapes is, it must be persuasive. Each of the women admitted participating in the stabbing and bludgeoning of their victims. The stories of all the killers — except for Manson, who has never admitted to anything — often Anthony DiMaria testifying at the same hearing change, with Atkins, for instance, on some occasions saying she stabbed Sharon Tate and on others saying she only held her while Watson did all the stabbing. If Watson’s version of the women’s actions in the murders is different than what he later communicated, it shouldn’t make a significant difference. Unless, perhaps, that information is somehow substantiated or documented in records that have never been shared with the public. So why the concern? A possible explanation that can’t be ignored is that the deputy DA and detective are actually withholding more conflicting — and damaging — information from the tapes than the information they shared with Tate and DiMaria. Ironically, at the height of their court battle for the tapes, the LAPD pointed out that if Watson was telling the truth when he said that the tapes contained nothing about unsolved murders — despite what his attorney told me — he should have nothing to fear by releasing them (as they evidently now do). And in response to Watson’s claim to the court, (in a June 2012 filing), that he wanted to protect the victims’ surviving family members from his grisly descriptions of their relatives’ deaths (“there should be no more victims,” wrote Watson), Debra Tate, who publicly advocated for the tapes’ release at the height of the court battle, pointed out that Watson has described those details innumerable times, first when he testified at his own 1971 murder trial, later in his book, and afterward at his fifteen parole hearings and on his website. It also seems relevant that when I asked Sequeira in our May 18, 2013, conversation whether Watson’s account of the murders on tape in November 1969 — the first-ever recorded account of the murders by any Manson Family member — diverged in any way from how he later described what happened, his answer was no. Additionally, the deputy DA, with whom I’d been regularly communicating for six years to that point, severed ties with me after that conversation. More curiously, perhaps, he missed his first Manson Family parole hearing (for Bruce Davis) in eight years this past spring—a hearing at which Sequeira could’ve been held to answer questions about the tapes on the record for the first time — and then abruptly retired from the DA’s office three weeks later. So it bears asking: Was Sequeira lying to me then when he said that Watson’s first account matched his later accounts, or was he lying to Tate and DiMaria nearly a year later when he told them that Watson’s 1969 account “minimized the involvement” of the women in the murders? And, either way, why a lie in the first place? (Sequeira and Jenks also told Tate and DiMaria at that meeting that they would be calling me next to schedule a similar meeting. That call never came). But most importantly: What is on the tapes that the Los Angeles District Attorney’s office and the LAPD doesn’t want the public to know? A new, perhaps truer version of the Manson murders than the sensational one presented by Bugliosi at trial and in Helter Skelter? And why isn’t the press — especially the LA press — reporting the strange and unusual fact that the LAPD refuses to go on the record about the tapes’ content? Perhaps the most troubling question of all, though, is: Would the LAPD and DA ignore evidence of unsolved murders on a tape if that tape also contained evidence that jeopardized one of their most prized convictions ever? One statement that Watson’s attorney Bill Boyd made to me in my taped interview now haunts me. In telling the tale of Watson’s eventual extradition to Los Angeles for trial (in late 1970), Boyd confided that Watson’s new attorney eventually learned about the tapes and began calling Boyd in an effort to get them. “But as soon as I’d hang up from him, Charles would call,” Boyd said (using Watson’s given name). “He’d say, ‘Ain’t nothing in there that’s gonna help this guy. Don’t send them.’ He very jealously guarded them.” Los Angeles law enforcement — with an assist from the LA press — is now doing that job for him. And it’s time the public knew why. Postscript: On August 8 — the 45th anniversary of the Tate murders — California Governor Jerry Brown overturned the decision by the California Board of Parole to release Manson Family member Bruce Davis. This is the third time the Parole Board has been overruled in their decision that Davis — convicted of killing Gary Hinman and Donald “Shorty” Shea — was suitable for release. As he had when he previously vetoed the Board’s decision in 2012 — and echoing his predecessor, Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger’s, reversal in 2010 — Brown declared that his decision was based on his belief that Davis had continued to “minimize” both his role in the killings for which he was convicted as well as his leadership in the Manson Family (former prosecutor Stephen Kay has called Davis “Manson’s chief lieutenant” and has speculated that Davis may have been responsible for at least one additional Family “murder”). Presumably, Watson — who was knowledgeable of the facts of the Hinman murder and a participant in the murder of Shea (though, never prosecuted for it) discussed those murders on the tape recordings made by Boyd. He also likely described Davis’s role in the Family. After the Board voted to release Davis on March 12, and four months before Brown’s deadline to either affirm or reverse the Board’s decision, Debra Tate had a meeting with Los Angeles District Attorney Jackie Lacey and several staff members to discuss the possible release of Davis. At the meeting, Tate told me the DA informed her that her office was considering sharing the Watson tape recordings with Governor Brown to assist him in making his decision. The District Attorney’s staff had discovered a “loophole” in the disclosure law, Tate said she was told, that would allow the Governor to listen to the tapes (or read their transcripts) without setting a precedent requiring that they also be released to the public. In response to an inquiry from Medium’s fact checker, the District Attorney’s office would neither confirm nor deny that a meeting with Tate took place. A spokesperson for Governor Brown’s office stated that the Governor never asked for, nor received, information about the tape recordings from the District Attorney’s office. At the same meeting that the DA’s office refuses to confirm took place, Tate says she was also told by Lacey that the decision not to release the tapes to the public was based on the recommendation of Jenks and Sequeira, who, along with the unnamed detective who transcribed them, are the only three people to have heard them.

This is listed reposted here for the historical record- you should read it in all its wonder and glory at this link.

Why doesn’t Los Angeles law enforcement want to reveal what’s on the 45-year-old Tex Watson tapes — and why isn’t the press reporting it?

By Tom O'Neill

Last year, on April 12, two Los Angeles Police Department detectives were about to board a plane at Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport with 44-year-old tape recordings of an infamous murderer describing his crimes to his attorney. Moments before they boarded the craft, one of the detective’s cell phones rang. “Are you on the plane yet?” Los Angeles county deputy district attorney Patrick Sequeira asked Detective Dan Jenks, LAPD Unsolved Homicides. “Don’t jinx it!” Jenks replied. Charles “Tex” Watson The tapes of convicted Manson Family murderer Charles “Tex” Watson, detailing the horrific killings he and several female accomplices had carried out on the orders of their cult leader, Charles Milles Manson, over two hot nights in August 1969, had been at the center of a court battle that went all the way to the Federal Court of Eastern Texas the preceding year. Fifteen days earlier, U.S. District Judge Richard A. Schell had affirmed a bankruptcy court judge’s ruling that, despite being recordings of a defendant describing his crimes to his attorney, the tapes were no longer protected by attorney-client privilege because the defendant and the attorney had later shared the tapes with an author who co-wrote a memoir with the imprisoned Watson that was published in 1978. Because of a miscommunication DDA Sequeira told me he’d discovered, Watson’s attorneys had been informed that they had thirty days to appeal Judge Schell’s ruling, when, in fact, they only had fourteen. When he learned of the error, Sequeira later told me, he told Jenks and his partner to be in Texas on the fifteenth day to take possession of the tapes — before Watson could discover the error and file an appeal on time (hence the jittery nerves of the Los Angeles law enforcement officials). But they procured the tapes and had them back at LAPD headquarters — secured in a safe purchased

especially for them — that same evening. Sequeira, who represented the state at all Manson Family member parole hearings from 2006 until last March, called me four days later to report the success of their secret mission. “Without you we wouldn’t have these tapes, let alone known they existed,” he said. “We owe you big time.” He would do his best to make sure I got in to hear them, he promised, ending one of the last conversations we would ever have. Watson and attorney Bill Boyd, Dallas, Texas, 1970 In November 1969, after being taken into custody near his hometown of Copeville, Texas, for questioning in the unsolved Tate-LaBianca murders that had occurred three months earlier, Watson was asked by his defense attorney, Bill Boyd, to describe his crimes with the Manson Family on tape. I learned about the tapes’ existence during an interview with Boyd in December of 2008. The 23-year-old former high school star athlete spared no “details,” Boyd told me in our taped phone call, describing how he and his accomplice, Susan Atkins (then 21), stabbed pregnant actress Sharon Tate to death as she begged for the life of her unborn baby. In addition to the “candid” and “very open” account of the murders of Tate and four visitors to her estate that evening (who were stabbed a total of 102 times and killed on the orders of Manson to ignite an apocalyptic race war he called “Helter Skelter”), Watson also recounted the equally gruesome murders of grocery store chain magnate Leno LaBianca and his wife, Rosemary, the following night. (Stabbed a total of 67 times, the killers left a knife and fork protruding from Leno’s corpse, carved the word “WAR” in his stomach, and, as they had the night before, scrawled phrases like “DEATH TO PIGS” and “HEALTER SKELTER” [sic] in the victims’ blood on surfaces of their home.) Tate House Victims: Voytek Frykowski, 32; Sharon Tate, 26; Steven Earl Parent, 18; Jay Sebring, 35; Abigail Folger, 25 (AP Photo) Leno and Rosemary LaBianca, 44 and 38, killed the next night in Los Feliz Boyd volunteered that Watson also described “other” murders committed by the Family that had never been discovered or connected to them by the authorities. Watson’s twenty-hour taped confession was the first recorded description of what would rank among history’s most horrific and baffling crime sprees. (The victims were strangers to their killers. At the trial, the prosecution would argue that Watson and his three accomplices — Atkins, a

San Jose, California native, who sang in her high school glee club; Leslie Van Houten, 19, a homecoming princess from Monrovia, California; and Patricia Krenwinkel, 21, a one-time Catechism teacher from Los Angeles — had been brainwashed by their “guru,” Manson, 34, an ex-con from Cincinnati who’d convinced them he was Jesus Christ and the Devil.) Atkins, Krenwinkel and Van Houten shortly after carving “x”s into their foreheads (mimicing Manson), on their way to trial at the Los Angeles Hall of Justice Written on the wall of the LaBianca home in the victims’ blood I wanted to listen to the tapes, not just because they allegedly contained information about unsolved murders committed by the group, but also because they constituted the earliest known narrative of how and why these killings occurred. In my (by then) nine-year investigation of the case for a project I was working on, I’d uncovered a significant amount of documentary evidence suggesting that the crimes — and the reasons behind them — were different than the official narrative presented by prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi at trial and in his best selling book about the case, Helter Skelter. But Boyd retreated from his original offer to let me listen to the tapes once it dawned on him how egregiously he had violated his client’s confidentiality. Less than a year later, he was dead of a sudden heart attack. Several years after that I began a lengthy crusade to get the tapes, first from his family and later from a court-appointed trustee who took possession of them after Boyd’s law firm went bankrupt. In March of 2012, I finally convinced the trustee that the tapes hadn’t been protected by attorney-client privilege for some time because in 1976 Watson had shared them — or a portion of them — with the co-author of his book, Will You Die For Me? The Man Who Killed for Charles Manson Tells His Story. (Watson’s death sentence was commuted to life in prison in 1972 when the California Supreme Court ruled the death penalty unconstitutional.) But because I’d also persuaded the trustee, Linda Payne, that it was possible the tapes contained evidence of unsolved murders — murders that weren’t disclosed in his memoir — she decided to release them to Los Angeles law enforcement instead. Upon learning of Payne’s plan to turn over the tapes to the LAPD, Watson — who insisted he knew of no other murders beside the nine the Family had been convicted of — waged a year-long battle in the Texas courts to prevent the tapes’ release. But he had a formidable foe in the LAPD. So determined was the LAPD to get the tapes that when it appeared that the case might be stalled in the courts, they took the unprecedented action of attempting to bypass the court’s authority by seeking a search warrant for their release. In the summer of 2012, I was summoned to LAPD headquarters, where officials listened to my complete taped interview of Boyd (to ensure his comments about “other” murders committed by the Family hadn’t been distorted or taken out of context) and used it as the basis of their warrant. When it was finally executed at Payne’s office in October 2012 by detectives from Los Angeles and the Fort Worth Police department, she called her own attorney, who immediately contacted Judge Schell. Schell issued an emergency order blocking the warrant and made sure to rebuke the officers in his written decision for attempting to circumvent his authority. (“The LAPD has provided no explanation as to why this court should shortcut the usual procedure for determining a bankruptcy appeal given that the investigation the LAPD wishes to reopen involves murders that occurred 42 years ago,” he wrote). From the warrant Regardless of his feelings about the LAPD, Schell ultimately ruled in the department’s favor, affirming a court decision from a year earlier that the tapes were no longer protected by attorney-client privilege and should be released. Fourteen business days later, according to Sequeira, on April 11, 2013, LAPD detectives returned for a second time to Payne’s office, but this time left with the tapes. But everything the LAPD has done since retrieving the tapes has raised questions that, while there might not be information about other, unsolved murders on them — the reason they were so assiduously sought in the first place — there may be something else on them, something far more significant, though damaging to the nearly half century-closed case. That question seems all the more relevant in light of a recent disclosure by two members of the murder victims’ families who had a secret meeting with two of the only three people who’ve likely heard the tapes — DDA Sequeira and Det. Jenks, the officer assigned to supervise the investigation (the third person is an unnamed homicide detective who transcribed the tapes). The startling information shared at that meeting may provide something of an explanation for the peculiar behavior of Sequeira and the LAPD since receiving the tapes. (Det. Jenks, former DDA Sequeira and the Los Angeles Police Department did not respond to multiple requests for comment by a Medium fact checker; at press time, the Los Angeles District Attorney’s office would only confirm that Sequeira had communicated with me about the tapes). Patrick Sequeira speaks to the press after Leslie Van Houten’s 2006 parole hearing In April 2013, when Sequeira excitedly called me to share the news that they had finally obtained the tapes, he was 60 and had spent the previous seven years representing the District Attorney’s office at all of the Manson Family members’ parole hearings. Shortly after taking over the job from Stephen Kay — the near-legendary DDA who’d successfully kept the five convicted Tate-LaBianca killers (Manson, Watson, Atkins, Krenwinkel, and Van Houten) behind bars for 35 years — Sequeira, like Kay, became a source for my project about the Manson Family. We frequently spoke and shared information about the case. Sometimes I even provided trial transcripts and old police reports he needed for parole hearings. I also put him in touch with the families of two lesser-known Manson murder victims — Gary Hinman, killed a week before Tate-LaBianca, and Donald “Shorty” Shea, killed two weeks after — when he needed them to appear at hearings for a sixth Manson Family member, Bruce Davis (who also killed on Manson’s orders, but didn’t participate in Tate-LaBianca). And, as my efforts to wrest the tapes from Payne escalated to the point where she decided to release them, she surprised both me, and Sequeira (who hadn’t been involved in the process), by contacting his office and offering them the tapes. Sequeira was open with me about how much they owed their possession of the tapes to my efforts. He said in that first conversation after receiving them that he wanted me to come in and listen to them with his colleagues to help decipher their content. “You know more about this stuff than anyone here,” he told me. The deputy was clearly excited at the prospect of opening new murder cases against one of the most notorious killing groups in California history. And, like Stephen Kay before him, he had become almost evangelically committed to keeping the Manson Family members behind bars for their remaining years on the planet. Certainly there would be information on the tapes — even if it wasn’t information about other murders — that would be useful in his increasingly difficult arguments against the parole of several Family members (particularly the now grayed and grandmotherly Leslie Van

Houten and Patrica Krenwinkel, both of whom renounced Manson in their earliest years of incarceration and have been model prisoners ever since). As in all our conversations since the news of the tapes’ existence went public a year earlier and the court battle began, Sequeira demanded I keep quiet about the latest development. He should’ve known he didn’t have to. Van Houten, 64, at her 20th parole hearing, June 5, 2013 Krenwinkel, 66, at her 13th parole hearing, Jan. 20, 2011 (Reed Saxon / AP) Since the story broke in May 2012 that the LAPD was seeking the tapes, I had refused to speak to the few reporters who’d learned I was the one who originally unearthed them. When the first stories appeared in the press quoting LAPD Chief Charlie Beck’s letter to Payne requesting the tapes — because, he wrote, “The LAPD has information that Mr. Watson discussed additional unsolved murders committed by the followers of Charles Manson” — I was surprised the reporters didn’t try to ferret out the source of Chief Beck’ s “information.” But I was pleased that the first one to discover it, NBC4 Los Angeles news reporter Patrick Healy (who originally broke the story of the LAPD’s interest in the tapes), honored my request to be omitted from his coverage in exchange for a possible future interview. The implicit understanding I had with Sequeira and Jenks from the outset was that if I kept silent about my knowledge of the tapes and their content — Watson’s attorney Boyd had shared specific details of two unsolved murders with me that the LAPD didn’t want publicized — I would eventually be granted access. But Sequeira was unusually worried that the LAPD’s possession of the tapes would leak. He was sure, he said, that if Watson learned they had them he’d try to get a court order forcing their return. I didn’t state the obvious: Watson had missed his deadline to appeal so the LAPD rightfully had them and was copying them as we spoke. If he somehow got a court order, they could send the originals and keep their copies. They’d still have the information they needed to pursue their cases. Instead, I assured him that I would continue to keep my counsel. A week later, on April 23, 2013, we spoke again, but this time he sounded guarded, much less effusive than usual. They were still copying the tapes, he said, and a detective from Unsolveds was simultaneously listening to them and taking notes. They hadn’t told him anything about what was or wasn’t on them, he added, and he didn’t think he’d get to hear them until the LAPD’s review was complete. He’d reminded Jenks that I should be brought in to help out, but Jenks was reluctant. They’d been “burned” by the press in similar situations before — he made a reference to the Robert Blake murder case — and Jenks didn’t want to take any chances. As if to reassure me that the strict precautionary measures weren’t limited to me (and, evidently, to him), he confided that he hadn’t even told his own boss — the DA — or his staff that they had the tapes. Two days later, Sequeira called me at 9:40 p.m. as he was driving to a ski vacation in Mammoth, California. He’d heard that Watson had filed an appeal for the tapes the day before — the last day of the thirty-day deadline — and wanted to know what I knew about it. I hadn’t heard anything, I said, but assured him it made no difference: They had the tapes and were reviewing them, and the time for the appeal had lapsed (it wasn’t thirty days, as Sequeira knew, it was fourteen — that’s why they had them). But he was worried, repeating his fear that Watson would try to get them through a court order. Though he still claimed not to know what was on them, I was beginning to have my suspicions. I waited until after Sequeira’s scheduled return from his week-long vacation before calling him again, on May 7. He hadn’t spoken to anyone yet, he said in a hurried voice, but planned to call Jenks that afternoon. He had another call he had to take, he added, but would let me know as soon as he learned anything. On May 9, I sent an email instead of calling him. “Can you throw me a bone?” I asked. It’d been four weeks since the LAPD got the tapes, I reminded him — certainly they’d shared something with him by now. He didn’t have to give me any specifics, just let me know if all the effort and waiting had been worth it. He replied that they hadn’t told him anything, and he hoped to know something the following week. I couldn’t help myself: “That’s pretty stunning information,” I wrote back. “You dispatch them to retrieve the tapes, speak to them while they’re in Texas in the process of getting them from Linda Payne and now, a month later, they still haven’t told you what’s on them?” I suspected Sequeira had played loose with the facts with me once before and I suspected he was doing it again. After I’d gone to LAPD headquarters the previous July to play the tape of the Boyd interview for the warrant he and Jenks were preparing, they’d executed it on October 3, 2012, without telling me. That was okay; it wasn’t my business to know. But when I asked Sequeira in an October 12, 2012, phone conversation when they were going to go to Texas with the warrant, he told me they’d changed their plans: They’d decided to request an ex parte meeting with Judge Schell and see if they could persuade him to release the tapes rather than try to get them with a warrant. A week after that conversation, the Associated Press broke the story that the warrant had been executed and blocked on October 5, 2012. Had Sequeira lied when he told me they’d changed their plans? They’d already done the warrant when we spoke, and it had been blocked by the judge. Since it hadn’t been discovered by the press, had he decided he could keep it from me? We didn’t speak for half a year after that. When we did, he claimed that the LAPD hadn’t told him about their failed effort until after he’d spoken to me. That, like the things he was telling me now, didn’t add up. He ignored the email but nine days later, on May 18, answered his cell when I called him at home on a Saturday. The verdict was in: There was nothing about unsolved murders or other murders by the Family on the tapes, he told me. The information had been relayed to him by Jenks, and he still hadn’t listened to them himself. “I don’t even know if they’ll let me listen to them,” he added. When I asked if there was anything on the tapes that diverged from the historical narrative of the crimes and how they occurred — information he might be able to use to impeach Family members at their parole hearings — he said no. Watson had told the same story he’d told at his trial, in his book, and at all his parole hearings, he said, and there was no new information. But what happened next shifted the balance in our relationship, and though I wasn’t aware of it then, ended it once and for all. I told him that the time had come for me to write a piece about the tapes for publication. The press still didn’t even know the cops had the tapes. I had an exclusive — in addition to the inside story of the battle for the tapes — and since there was nothing of value on the tapes to law enforcement or the parole board, there was no longer any reason to keep quiet. He exploded.

“Don’t do that! If Watson finds out we have them he’ll try to get a court order to get them back.” But what difference did it make? I replied. There was nothing on them. Then I shared something with him he didn’t know yet. After he called me expressing worry about Watson’s appeal three weeks earlier, I emailed the trustee who’d had the tapes to see if Watson’s attorneys had been notified that they’d been transferred to the LAPD. They had, she responded. So Watson knew, I told Sequeira, for at least two weeks, possibly longer — but that didn’t deter Sequeira in the least. I should wait until his office got a copy of the tapes, he said. That way if Watson sued for them he’d have to sue both the police department and the district attorney’s office for the tapes. The LAPD would never fight the suit, he said, “but we would.” Nothing he was saying made sense. He’d just said he didn’t know if he’d ever get to hear the tapes; now he was telling me I should wait until he got his copy? And, again, what difference did it make if there was nothing that could be used in either a criminal investigation of other murders or at parole hearings? Nonetheless, I decided to acquiesce to his demands. I couldn’t preclude the possibility that there was, in fact, a murder investigation underway that he couldn’t tell me about. I also wanted to hang on to the shred of a chance I still had to listen to them. To alienate him now would eliminate that possibility forever. But when I said I’d at least begin the lengthy process of filing a California Public Records Act request with the Discovery Section of the LAPD to listen to the tapes, he erupted again. The request would alert the media to the fact they had the tapes. Again, I said, so what? There’s nothing on them. He still had no answer, just the implicit threat that if I did anything that resulted in the press — not Watson now, because Watson knew — learning that the LAPD had the tapes, I’d never get to hear them. “Just be patient, Tom,” he pleaded. Though it made no sense, I promised to continue to be silent. It was the last conversation we ever had. So it was hardly a surprise when, five days later, the LAPD provided a different narrative to the press when it was finally reported that they had the tapes. The Associated Press broke the story — “Manson Disciple’s Tapes Being Analyzed by LAPD,” ran their May 23, 2013, headline. Beneath it: “Detective David Holmes said the department has had the tapes for a couple of weeks and Robbery Homicide and the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office are analyzing them.” The next day’s Los Angeles Times followed up, reporting: “LAPD Cmdr. Andrew Smith said the department’s elite Robbery Homicide Division, along with Los Angeles County prosecutors, are starting to review…tapes of conversations between one of Charles Manson’s most fervent followers and his late attorney to see whether it can help solve more cases from that period.” Then the papers and the TV news outlets stopped covering the story. More than a year has passed since the May 23, 2013, AP report that the LAPD had the tapes for “a couple of weeks” and — with the DA office’s assistance — were “starting” to analyze them. Except for the stories around the globe repeating the AP’s scoop in the 24 hours following it, not a single additional story has appeared in the mainstream media about the tapes. Locally, NBC News4 Los Angeles filed a dozen stories on the Texas court battles between May 24, 2012 and May 24, 2013; the Los Angeles Times ran five stories between May 24, 2012 and May 25, 2013 (one on the front page) and hosted an online discussion of the blocked search warrant moderated by its city editor and chief crime reporter, Richard Winton. Yet neither of them — nor any of the local outlets that so feverishly covered every development in the court battle for the tapes — has published or broadcast a follow-up story on what might or might not be on them. By the autumn of 2013, months after Sequeira had stopped returning my calls and emails, I contacted five local