Chapter 21

In late August, while Charlie’s dune buggies roared across the

“Pig” was the word Charlie had used to describe

Near the end of September, Manson was making numerous forays into Death Valley, looking for caves, exploring the terrain, choosing strategic hideouts in which to store his burgeoning supplies – still searching for the mystical (hole” in the desert where the Family could go to wait out the ravages of Helter-Skelter and make “a new beginning.” Traveling in caravans of three to five dune buggies, he led these expeditions for days at a time, leaving Clem and Bruce and a few girls behind to watch the Meyers ranch in his absence. At one point Charlie asked me to search for “the hole” by diving with scua gear into Devil’s Hole, a vast, murky water-filled cavern just across the

Still, I was playing both ends against the middle. I had accepted favors from the Family—playing music with them, made love to Snake, and at times had listened to Charlie’s Helter-Skelter rap, still half-believing it was true. I didn’t want to do this; more, it was like an unconscious reflex born of habit. It was also as Crockett had said, “foolish” –a game I was playing that was rooted in conditioning and based in part on my fear of completely severing ties with the Family, even after I sensed there was nothing left to salvage. Accepting this was to admit I had been a fool, a dupe, just another of Charlie’s pawns; which I had. Describing my feelings is not easy, since they changed often and there were many levels and much confusion. Inside, I told myself, “They did not kill Shorty.” I’d seen him less than a month before. I’d waved and he’d waved back. Charlie was merely trying to manipulate my fears. It was easy to say, “Yeah, we had to kill Shorty.” But where was the proof? Charlie was always boasting of his macho exploits, but I had never actually seen him so much as step on a bug. Yet, deeper down, I sense it was true. I’d felt it. At that point I still had no idea how deeply programmed I was, how much work it would take to free myself.

Early one morning sometime around the first of October, Charlie spotted me on the hillside and hiked up to where I stood surveying the valley while sipping a cup of hot coffee. He reminded me that a year had passed since we had first come to the Barker Ranch as a Family. He told me he was taking an expedition over to the

“You don’t have to go all the way with them or nothin’, just show them how to get up there—that’s a pretty tricky trail, you know, and they’ve never been up there.”

“I don’t mind, Charlie,” I said.

An hour later I met the girls at the head of Golar Wash and we started for the Lotus, a defunct gold mine located about midway up Golar Canyon at the top of the mountain, a strategic spot from which to survey the entire valley. The climb from the base of the wash to the mine and the small stone dwelling beside it followed a steep, twisting trail, replete with switchbacks and spots where the footing was treacherous. Halfway up, Sherry and Barbara announced they had left their packs and canteens at the bottom of the trail and went back to get them, and I continued on to the mine with the girls. After helping them make camp, I hiked down the quebrada and back four miles to the Barker ranch.

Later that afternoon when Crockett, Brooks, and I went down to retrieve supplies from the foot of the wash, Sherry and Barbara Hoyt suddenly appeared from behind a rock, claiming they wanted to hike out of the valley and go back to

Crockett listened while they confessed their fears. His face expressionless, his eyes scanning the alluvial fan that stretched twenty-three miles toward Ballarat; he reached over and felt the canteen Barbara had strapped to her waist.

“Getting dark,” he said. “Might as well go up with us, think this out.”

That night we sat around the table drinking coffee and listening to Barbara and Sherry. Both girls were relative latecomers to the Family. Barbara arriving at

Barbara’s voice was high-pitched and agitated. “Charlie says we’re free, that there are no rules, but we’re not free. He says we can do what we want, but we can’t. He said about two weeks ago that if we tried to leave he’d poke out eyes out with sticks. He—“

All we want is to go to Ballarat,” Sherry added. “From there we can get to

After the girls had gone to sleep, I discussed it with Crockett and decided that I would take them to the base of the canyon, drive down the gorge in the power wagon, and leave them at the edge of the valley.

“Give ‘em enough water and tell ‘em to keep a steady pace…they won’t have no toruble…we’ll feed ‘em a good breakfast in the mornin’.”

At noon the next day I dropped them off at the edge of the canyon, then headed back in the power wagon. I drove slowly, bouncing and weaving along the valley floor, avoiding eroded gullies and boulders. The sun blazed off the hood of the car, casting a blinding reflection. To cut the glare I put on a pair of dark glasses that were lying on the dashboard; it was well over 120 degrees in the shade, the air bone-dry. Sherry and Barbara would have to go slowly in the heat, but they had enough water and I knew from experience that barring unforeseen circumstances, they would make it with little problem.

I was nearing a point just south of Halfway House Spring, a particularly rocky stretch of ground, almost directly beneath the Lotus Mine, when something distracted me. I looked to my left just as Charlie’s head appeared above the rocks in the gully, where he’d been filling his canteen. At the very instant our eyes met, the left rear tire popped, the echo reverberating against the walls of the canyon. It was as if all the pressure generated by our gaze had caused the blowout. I sat stunned, listening to the hiss of escaping air as Charlie scrambled toward me over the rocks. He was shirtless and had Snake’s binoculars around his neck. I knew at once he’d been watching me from the Lotus Mine. He had a shit-eating grin on his face as he approached me, dusting off his buckskins with his hands. He took the hat he was wearing and held it out as though appraising it, then looked at me.

“Thought you were headed out to Saline?”

“Just wanted to check on the girls,” he said evenly. He leaned against the fender of the truck and put his hat back on. “Hey brother,” he drawled, “you wouldn’t lie to me, would you?”

“No.”

“You didn’t take Barbara and Sherry down the canyon, did ya?”

I looked Charlie dead in the eye.

“No.”

Charlie grinned. We both knew I lied, yet for some reason he reacted as though I had said yes, as though my lie had been programmed by him. That was Charlie’s way. When things went against him, he often acted as though he had programmed it, so that no matter what was said, he was in control.

“Well,” he said, “you want to drive me down there so we can pick them up?”

“Got a flat…no jack.”

“How ‘bout walkin’ with me?”

“I gotta get back to the ranch…get this truck fixed.”

He gave me a long, hard look. “Guess I’ll have to get them myself.” With that he turned and trotted down the wash.

Frightened and confused, I scrambled up the wash. Sherry and Barbara had a three-mile start on Charlie, but they didn’t know he was after them, and we’d told them to conserve energy and go slow. Had the car been running, we’d have caught them in twenty minutes. I figured they had a fifty-fifty chance of making it. If he did catch them, I didn’t know what he’d do. But it wouldn’t be pleasant. For the first time I was really scared. Up until then, my actions had all been open and aboveboard insofar as Charlie was concerned; there was still the implication in the game we were playing that I might be won back to the fold, that Charlie might still invalidate Crockett. But helping his girls escape – I couldn’t have crossed him in a more blatant fashion. I had an impulse to go back and find him. I felt like a condemned man, sensing that unless I confronted him right away, I’d never be able to face him. But I wanted to talk to Crockett.

“I think you’re right,” Crockett said after listening to what had happened. “Better go back and meet him… tell him straightaway. That lie puts you on the run, and the longer you got it hangin’ over ya, the more it’s gonna wear ya down.”

I filled a canteen and put on my boots. Crockett went out on the porch with me.

“What you can do,” he said, “is process yourself on the way down there so there’s minimum tension when you meet him. You just imagine everything that could possibly happen when you see him, everything, as vividly as you can…all while you’re walkin’; that way you run all the excess tension and energy off the actual confrontation, so it’s cleaner. See what I’m drivin’ at?”

“Yeah, I see.”

“I t ain’t like you imagine they’re gonna happen…it’s just takin’ the tension off the possibilities, like makin’ them pictures go away, so you don’t bring them up when you get there…you just do it.”

I knew Charlie had eight or nine miles on me, but I took off anyway. It was dusk by the time I reached the base of the canyon and started out across the valley. I must have gone at least ten miles when I realized the futility of trying to catch Charlie at night. I knew, too, that if I remained in the valley he might not see me when he returned to

About midmorning the next day,

“Are Sherry and Barbara with him?”

“Naw…why?” Barbara asked.

“Just wondered.” I got out of the sleeping bag and started rolling it up.

“You need a ride back up?”

Go to talk to Charlie.”

For the next hour I waited, still processing all the confrontation possibilities in my mind. I was apprehensive but in control. It must have been close to noon when Charlie finally rumbled into view about twenty yards from where I sat hunched against the cool wall of the canyon. The moment he spotted me, he stopped the buggy and leaped out with a forty-five pistol in his hand.

“You motherfucker,” he shouted, “I should blow your head off!”

/my heart was thudding, but I didn’t panic. Charlie’s eyes were bloodshot, his face windburned and dry. He pushed the barrel into my chest.

“You ready to die?” he bellowed.

I held my breath, but didn’t flinch, then said, “Sure, go ahead…I fucked up, maybe I deserve it.”

“I’d be doin’ you a favor!”

“Maybe so.”

Then he thrust the gun at me and I took it. “Maybe you ought to kill me…see what it’s like!”

“No, Charlie, you know I don’t want to do that.”

“How ‘bout if I just cut you a little!” He pulled out his knife and shoved the point against my throat. I took a step back. “Well, then, you cut me!” He offered me the knife and I shook my head.”

“You know what I ought to do…I ought to kill that fucking old man…he talked those girls into leaving.”

“No, he didn’t. All they wanted was food and water. They were leaving anyway.”

“Well, he put discontent in their heads…Get in!”

Charlie pointed toward the dune buggy, and we both climbed in. He laid the forty-five in the back and fired up the engine. “I caught up with those girls in Ballarat,” he said, without looking at me. “They wouldn’t talk…I gave them twenty bucks and sent them back to Spahn’s”

Moments later, Charlie was laughing. He put his arm around me. “Nothin’s changed, you know, between you and me. What goes round comes round; we’re still brothers, and no redneck piggie miner is gonna change that. ‘Cause one day he’s gonna wake up and find that he just ain’t here.”

Near the top of the canyon we came up behind Juan and Brooks hiking toward the ranch. Charlie stopped and they climbed in.

“Where you been, Juan? Seems like I hardly see you anymore.”

Juan didn’t reply, but he held Charlie’s gaze through a rearview mirror. Charlie pulled up at the gate and stopped. We all piled out.

“Say hello to that old man for me,” he said. Then he lurched forward in a swirl of dust, and we headed into the yard as Crockett came down to meet us.

5 comments:

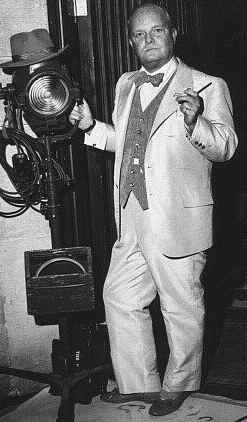

Capote's thing with BB was the whole copy-cat angle....that the murders were committed to free BB because the police would say, "hey, looks like we got the wrong guy on Hinman!" Pretty pathetic, especially when the cops couldn't even make the connections themselves...dopes.

The Watkins book also reminds me that if the cops had only released the fact that "Healter Skelter" was one of the words written in blood at the La Bianca's that the police could have pretty well wrapped these cases up right quick!

Thanks Col...

=^..^=

The interview is in an anthology book of his writings, interviews, etc. I found it no problem at my friendly neighborhood library and read the BB interview right there in the stacks. Now, if I could only remember the book's title I'd tell you....

Ah yes...it is "A Capote Reader" where you'll find the BB interview...now I remember.

Thank you, much. I'm around everyday.

Post a Comment