...Truth has not special time of its own. Its hour is now — always and indeed then most truly when it seems unsuitable to actual circumstances. (Albert Schweitzer).....the truth about these murders has not been uncovered, but we believe the time for the truth is now. Join us, won't you?

Friday, August 14, 2009

History Channel Doc

Wow- what an awful documentary. They actually made the story boring. It takes real skill to do that.

Random Thoughts

- how seriously can we take you when you state on a fucking title card that Spahn Ranch is in Benedict Canyon which is 20 miles away?

- I know you couldn't afford to license Beatles songs, but do you really expect anyone to believe Charlie listened to the WHITE ALBUM on fucking HEADPHONES?

- Gypsy is back to tell us her lies...she was lying in all that Henrickson footage and News footage then but she is telling the truth now- or something. I love Charlie kicking her though- such BS but I was cheering HIM on.

- Who is that one tooth freak that keeps appearing? No one in the Family was inbred.

- Jakobsen is now called Shapiro? Because any Jew will do?

- They are using the Tate Home Movies that I posted before YOUTUBE scum (Thanks Savage) took them down.

- Debra is there but doesn't get the chance to make too much up.

- Who knew that Linda Kasabian had become a transexual? I missed that part. She sounds like she is reading a script. No mention of her continued legal troubles, or of Tanya growing up to become Lady Dangerous. Of course.

This played in the UK and Canada and will play in USA in a month. And still suck.

Thursday, August 13, 2009

Debra Pimps

Restoring Sharon Tate

'ICON: Life Style Love Sharon Tate' celebrates the actress as 'a style icon, not a tragic headline,' according to artist Jeremy Kenyon Lockyer Corbell.

By Steffie Nelson

Her closet may have been full of designer dresses, but Sharon Tate was a flower child all the way down to her toes. Most comfortable barefoot, she used to skirt the "shoes required" laws in snooty late '60s Beverly Hills by looping leather string around her toes and across the tops of her feet, and then tying the ends around her ankles. Voila: sandals. Even the Malibu Barbie doll, said to be inspired by the actress and her bikini-clad character, Malibu, from the 1967 beach comedy "Don't Make Waves," was barefoot in her box.Details like these seem trivial when held up against the events of Aug. 9, 1969, when Tate, 26 years old and eight months pregnant with her husband Roman Polanski's child, was murdered by Charles Manson's followers in her Benedict Canyon home. Indeed, it's difficult to utter Tate's name without Manson's following close behind, and it will be even more so on this 40th anniversary weekend, as the face of the cult leader, now 74, looms large in the media.

Is it possible to remember her now as the free-spirited natural beauty who prided herself on wearing the shortest miniskirts in town, instead of as the victim of a horrific crime? Santa Monica artist Jeremy Kenyon Lockyer Corbell is attempting to tease apart the intertwined images with the exhibition "ICON: Life Style Love Sharon Tate," which celebrates, in his words, "a style icon, not a tragic headline." Taking over an 8,000-square-foot space in Culver City this weekend, the multimedia show expands upon a series of photographs Corbell shot last year of up-and-comer Lauren Hastings modeling pieces from Tate's wardrobe.

The clothes came courtesy of Tate's sister Debra, who shared them with the public for the first time on a 2008 episode of "Inside Edition." "No one ever really, in her opinion, cared to know about this other part of [Sharon's] life, her passion for clothing and her sense of style," explains the program's producer Esmeralda Servin, who had come to know Debra, now 56, through other stories (most related to Manson family parole hearings). Debra, she says, was immediately receptive to the idea of focusing on the clothes, with Servin and in the Corbell project that flowed from it.

For the cameras, Debra pulled plastic-wrapped pieces from a cedar hope chest, including the high-necked, puff-sleeved, micro-mini wedding dress that Sharon designed for her 1968 marriage to Polanski. News footage from the couple's reception at the Playboy Club in London -- attended by L.A. pals including Warren Beatty, Candice Bergen, Mia Farrow and many others -- shows them looking like some kind of mod fairy-tale prince and princess; the diminutive auteur (only 5 foot 5 to her 5 foot 6) in a frock coat and cravat, feeding cake to his bride, fresh white flowers woven into her elaborate do. Her beauty -- which her husband claimed she was "embarrassed by" -- is timeless, yet she effortlessly embodied her time: glamorous starlet in heavy false eyelashes and fur one moment, haute hippie with beach-blond hair and languid gaze the next.

It's that image that still resonates powerfully in the design world, where, at least in some quarters, she seems to survive in memory more as muse than martyr. "It wasn't only her looks, it was the way she carried herself," says Dear Creatures' Bianca Benitez, who invokes the "Valley of the Dolls" ingenue in her spring 2009 collection. There's even a pair of high-waisted denim "Sharon Shorts," although Tate herself was partial to dresses.

Each piece worn by Hastings captures a different side of Tate, and of the '60s: There's a short, black mink coat with the name "Sharon Tate" embroidered inside; an Ossie Clark tunic worn with an op-art Yves Saint Laurent scarf; a full-sleeved paisley minidress by British hippie chic designer Thea Porter (who famously put Talitha Getty in a caftan); the black lace, strapless Christian Dior gown Tate wore to the premiere of "Rosemary's Baby"; and the simple, flowered sundresses she wore around the house that fateful summer at 10050 Cielo Drive.

Resurrection Vintage owner and designer Katy Rodriguez, who lives nearby, has visited that address "many times." "She is a huge inspiration to me," says the designer, who has played with '60s silhouettes in several collections. "She is the ultimate L.A. woman. There is no other."

Rodriguez tells a story about visiting her friend Nils Stevenson in London. "He was the Sex Pistols' PR person in the '70s and his brother is the rock photographer Ray Stevenson. Nils had a black-and-white image that Ray shot of Sharon at a party in the '60s. She looked so glamorous in something shimmery with that big hair. We had more than a few drunken nights staring at the photo and saying the same thing: They just don't make girls like that anymore. Everyone loved her, even the punks."

Undeniably, the darkness of Tate's fate somehow throws her into brighter relief. But, Rodriguez asserts, "The Manson connection is only one part of her story. Her life and her promise was as compelling as her death. She traveled between light and dark. . . . It's what makes her so interesting. Other people died that night, but we gravitate toward Sharon."

Tate's path certainly didn't follow the storybook fantasy of her wedding. By 1969 she was considering divorcing the womanizing Polanski, according to author Greg King, and lamented the direction her film career had taken. To her friends, Sharon disparaged her media image as "sexy little me."

"She did these movies that critics like Pauline Kael and others made fun of," notes Adam Parfrey, a book publisher whose catalog encompasses Hollywood history as well as the Manson Family. "She wasn't a star; she was a starlet. She never had a chance to demonstrate much acting prowess."

Star billing came only after her death, when "Valley of the Dolls" and the Polanski-directed horror spoof "The Fearless Vampire Killers" were rereleased within days of the murders, preserving her image in the bloom of youth and possibility.

Corbell spent more than a year pondering Tate's story as he reworked the photographs he'd shot with an old press Polaroid camera: enlarging them, painting on them, and embedding them in antique window frames. He believes our fascination goes deep, to a subconscious level. "Is she an icon just because of her death," he asks, "or is she an icon because she represented something -- some spirit of purity or love -- that was brought to light by the way she died?"

The 32-year-old, self-described "accidental artist" freely admits that when he was first approached by Servin about doing the shoot, he found the concept a little creepy. "I made that same equation, Sharon = Manson." But as he grew to understand Debra Tate's situation -- robbed of almost every positive memory of her sister -- Corbell "saw the potential to tell a story that was bigger. That's what I care about as an artist."

Asked why he chose the anniversary of Tate's death to celebrate her life, Corbell says that he'd actually considered having the show on her birthday, "but what I'm trying to do is change the equation on a day that acts as this launchpad to repeat the negative mantra of fear. I'm trying to turn fear into hope."

ICON is open to the public from 1 to 5 p.m. today at High Profile Productions, 5896 Smiley Drive, Culver City.

Monday, August 10, 2009

General if Decent

The Manson murders — 40 years later

TERROR: The brutality of the killings destroyed a period of innocence and changed the city forever.

Forty years ago on Aug. 8, from his ranch in the San Fernando Valley, Charles Manson dispatched a band of devoted fanatics on a high-profile killing spree that shocked the world and terrified Angelenos, who never left their doors and windows unlocked again.

"It was a scary thing back then and it continues to this day," says Vincent Bugliosi, who successfully prosecuted the Manson "family" for one of the city's most notorious murder binges.

Among the seven victims of the two-day murder spree was actress Sharon Tate, the wife of director Roman Polanski, who was eight and a half months pregnant at the time.

As details of the crimes emerged, fear spread in a city that simply could not comprehend the sheer brutality of the murderers, many of whom were long-haired young women who could be mistaken for peaceniks.

Six of the seven victims were stabbed a total of 169 times and the seventh was shot dead.

"It had a definite effect throughout L.A., and it did induce fear throughout the city," Bugliosi said.

In the early hours of Aug. 9, 1969, the Manson family killed Tate, 26, and four others in Benedict Canyon - coffee fortune heiress Abigail Folger, 25; celebrity hairstylist Jay Sebring, 35; Polish film director Voyteck Frykowski, 32; and Steven Parent, 18, friend of the caretaker at Tate's home.

Manson stayed at the Spahn Ranch in Chatsworth while his devotees committed the Tate murders. The following night, Manson went

The killers also scrawled "Healter Skelter" and "Pigs" in the victims' blood at both murder scenes - references to the Beatles song "Helter Skelter" released the year before, which the killers misspelled, and a slur directed at police and the white establishment.

"There were people in L.A. back then, in 1969, who didn't lock their doors," says Bugliosi. "It was a certain period of innocence to a certain degree and that all stopped with the Tate-LaBianca murders."

James Schamus, screenwriter and producer of the upcoming film "Taking Woodstock," grew up in North Hollywood, in the hills right off Mulholland Drive, and remembers the fear that overtook the city.

"I was under lockdown, as were all of my friends because just a few days before, the Manson family went on a rampage in the neighborhood," he recalls. "My parents were like, `You're not going out!'

"They didn't know it was the Manson family until they were arrested a couple of months later. But they knew that they were hippies who did it, because they used the blood to scrawl `pig' on the wall."

Four decades after what Bugliosi calls an "orgy of murder," the legacy of Manson looms disturbingly over pop culture and an entertainment capital that still seems to be coming to grips with the madness of the convicted mass murderer.

Manson was given the death penalty along with Charles "Tex" Watson, Susan Atkins, Patricia Krenwinkel and Leslie Van Houten. When the courts overturned the death penalty, their sentences were commuted to life in prison.

Another family member, Linda Kasabian, who stood watch at the Tate murder site, turned state's evidence. She served no time.

Today, Manson, 74, short and balding, bears little resemblance to the long-haired, bearded menace whose likeness became a pop culture icon. What does remain is the devilish stare and the swastika, which he carved on his forehead while on trial.

"But the shadow of Charles Manson continues to haunt our nation's psyche, especially in Los Angeles," says Dr. Carole Lieberman, a psychiatrist on the clinical faculty at UCLA who specializes in violence and terrorism.

"Why? First, the scattered contamination of spots in Los Angeles where the Manson family lived and killed. From Malibu to Los Feliz, the San Fernando Valley to Venice, and numerous places in between.

"Secondly, the randomness or `helter skelter' aspect to the crimes, which causes us to realize that we are not safe, even within our fancy homes."

Though America has seen dozens of notorious serial killers since Manson, the fascination with this Ohio-born drifter who spent most of his life in reform schools and behind bars persists.

"The main reason for the continued fascination at such a late date (is) the murders were probably the most bizarre in the recorded annals of American crime," says Bugliosi, who later authored a best-selling book about the crimes - "Helter Skelter."

Manson construed the expression as the harbinger of an apocalyptic race war he hoped the murders would trigger.

"For whatever reason," says Bugliosi, "people are fascinated by things that are strange and bizarre. Manson himself. Just how many Charles Mansons are out there?

"The incredible motive: To ignite a war between blacks and whites, an Armageddon. The killers printed words from Beatles songs in blood, mind you, at the murder scene. The fact that these kids (Manson's killers) came from average American homes. Who would ever dream that, of all people, they would be mass murderers?"

Today, dozens of bands, especially in Europe, play songs penned by Manson or that were written in support of the mass murderer. The Internet has millions of pages devoted to him. Manson cult groups abound throughout the world.

At the Spahn Ranch in Chatsworth where Manson and his followers lived while in the Valley, locals say they occasionally see visitors searching for the Santa Susana Mountain location, once a western movie set and now fenced off and owned by the state of California.

"Some people don't think Manson was crazy but a genius to be able to manipulate people like he did," says horse trainer Candy Cooper who lives not far from the ranch. "People were horrified by the killings and the way they were done, and they come here, I guess, looking for where the man who masterminded that lived."

Holly Huff, who lived in Box Canyon where the ranch was and had just graduated from high school when the murders took place, remembers that Manson and his clan had taken control of George Spahn's movie ranch, over the objection of the ranch's caretaker.

"George was blind, and the story was that they had seduced him by having the girls have sex (with him)," says Huff, who remembers that the caretaker soon mysteriously disappeared.

"I don't think anyone ever heard from him again."

Huff also recalled that in the months before the murders, many residents of the Box Canyon area complained of returning to their homes and finding their furniture and furnishings moved around - though nothing was taken.

"I think they called it `creepy crawling,' and many thought (the Manson family) was responsible," she says.

Then, just days before the killings, Huff said, a friend found his garage looted of equipment used to cut steel. It was common knowledge the Manson family was converting old cars into dune buggies.

"He was gonna go up to the ranch and confront them, but didn't," said Huff. "And it's probably good that he didn't."

Others with an interest in Manson also look for the former site of a two-story house at 20910 Gresham St. in Canoga Park, not far from the Spahn Ranch, where the Manson family lived in late 1968 and early 1969.

That house was known to Manson's followers as "The Yellow Submarine," referring to another Beatles song.

"It was like a submarine in that when you were in it, you weren't allowed to go out," Watson tells Bugliosi in his book. "You could only peek out of the windows."

Today, the house is gone. The former single-family home neighborhood has been converted to apartment buildings - but memories of Manson and his family remain.

Longtime Chatsworth resident Virginia Watson remembers that the Manson family became a fixture in the area in the months leading up to the murders.

"They weren't here long, but they made a big impression," says Watson, who is now curator of the Chatsworth Historical Museum. "They were like a gang, and they would come in to shop at the Hughes Market or the Arco gas station.

"They would steal things from the market, and you would see them scavenge through trash cans, and everyone would stay away from them as much as possible."

But it was not until Manson and the family were linked to the killings, says Watson, that local residents realized how close they had been to potential harm.

"Before they had just seemed like renegades," says Watson. "But when we found out what they did, I think we realized we had been right in avoiding them as much as we could."

No Show Without Punch

Taking on Charles Manson

No matter what else he does, the lawyer and author will always be known for prosecuting the infamous murder case.

August 8, 2009

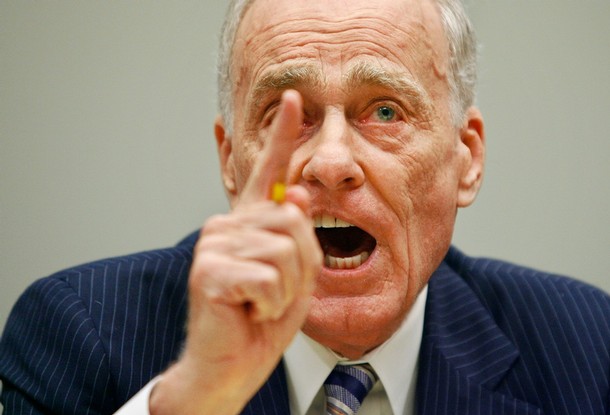

Vincent Bugliosi has moved on, but the world hasn't. Forty years after the impossibly grisly Tate-LaBianca murders, he is still "the Manson prosecutor." This, in spite of his many books since, arguing with magisterial fury about the JFK assassination, the O.J. Simpson trial, the Bush vs. Gore case and now the Iraq war.

His book about the murders masterminded by Charles Manson, "Helter Skelter," written with coauthor Curt Gentry, hasn't been out of print since it appeared in 1974. It's blurbed as the bestselling true-crime book of all time, at what Bugliosi figures is about 7 million copies. His 2007 JFK book, "Reclaiming History," got its start in a 1986 mock trial on television, in which Bugliosi prosecuted Lee Harvey Oswald, using actual assassination witnesses, and proved that Oswald alone killed the president. It has sold considerably fewer copies than "Helter Skelter," but, as he says, "if you want to make money, you don't put out a book that weighs 7 1/2 pounds and costs $57 and has over 10,000 citations and a million and a half words."

Bugliosi still writes voluminously -- and without a computer -- but he's had to put down his pen for the moment because journalists like me are swarming around, asking for his insights, 40 years on, about the 1969 slaughters, now known the world over as the Manson murders, and their chief instigator, the hideously and evidently perpetually fascinating Charles Manson.

Aren't you tired of people asking about Manson?

I've actually had a copilot come out of the cockpit on a trip from L.A. to New York and ask me about Charles Manson. I was at a book convention, in a cab -- on one side of me was Arthur Schlesinger, on the other side was William Manchester, real heavyweights. All they were doing was asking me about Charles Manson. The only thing that enables me not to be bored is the people talking about it -- they're so interested. The durability of this case is just incredible.

Why? There have been more prolific murderers and gorier killings since then.

Many factors. The single most important is that the murders were probably the most bizarre in American crime, and people are fascinated by things that are strange and bizarre. It's not the brutality -- they were extremely brutal murders, but like you say, there have been more brutal murders. Not the prominence of the victims. Another reason -- the very name "Manson" has become a metaphor for evil, and evil has its allure.

So he's become the Hitler of murderers, by which all other murderers are measured?

You said it -- I can't say that. Just one [example] among many: Mike Tyson's applying for renewing his boxing license before the boxing commission in Nevada. He says, "Look, I'm a bad guy, but I'm not Charles Manson." His name is used in that context. Now [O.J.] Simpson -- you don't hear [that] about the Simpson case. It was kind of a garden-variety case. The Manson case just never ends.

What do you make of the enduring cottage industry of Manson shirts, music, posters?

He's got this image, almost a glamorous outlaw type, an anti-establishment figure, like Dillinger or Jesse James, but [kids] really don't know who he is. They don't know how evil he is. I think if they really knew who Manson was, they would not be wearing those shirts.

In 1972, the Supreme Court overturned the death penalty, including those in the Manson case. Are you sorry he and the others weren't executed?

Well, that would have been the proper sentence. The execution of a condemned man is a terrible thing, but murder is an even more terrible thing. They deserved to die, these people, and I asked for the death penalty and I would do so again. I don't know if "sorry" is a good word -- I'm disappointed, of course, particularly with respect to Manson.

Yet you also supported Manson family member Susan Atkins' parole request not long ago, and got a lot of grief for it.

The visceral response would be, "Well, she showed no mercy so she gets no mercy." But there are several things which militate against that easy conclusion. She's already paid substantially for her crime, close to 40 years behind bars. She has terminal cancer. The mercy she was asking for is so minuscule. She's about to die. It's not like we're going to see her down at Disneyland.

If you were writing your own Wikipedia entry, what would you put first?

I guess it would be [Manson]. It's a shorthand way of defining me, no matter what else I do. I can no more separate myself than I can jump away from my own shadow, and it tends to dominate the other things I've done.

What are you proudest of?

Certainly my magnum opus, "Reclaiming History." It's the most important murder case in American history. I put the best of what I know as a prosecutor into that book. It was just moonshine, these conspiracies. All these allegations made no sense whatsoever, so I decided to set the record straight. Oswald killed Kennedy. He acted alone. Because of these conspiracy theorists who split hairs and proceeded to split the split hairs, this case has been transformed into the most complex murder case in world history. But, at its core, it's a simple case.

"The Betrayal of America," attacking the 5-4 Supreme Court decision in the disputed 2000 presidential election -- not at first blush a case for a criminal prosecutor.

I'm not a political activist. But whenever something is so egregious, I jump in. Even many Republican scholars [said], "The court should be ashamed of itself; we've lost respect for the court." And I kept saying, "That's all? You lost respect?" These five [justices] are among the biggest criminals in American history. How dare these people have the audacity to do what they did? I think I made my case pretty well that these people deliberately tried to steal the election.

And now your latest book, "The Prosecution of George W. Bush for Murder," published in May, makes a murder case against Bush for waging war unnecessarily and shows how he could be prosecuted for it.

Bush [told] unsuspecting Americans the exact opposite of what his own federal intelligence agencies told him. What could be more criminal than the Bush administration keeping the all-important conclusion from Congress and the American people, with the lives of millions in the balance?

Every day, I think of those people in their graves now -- no one is fighting for them. You can see that I'm upset. I don't like to see anyone get away with murder. O.J. Simpson got away with two, and I wrote the book "Outrage." If I can get that angry over one or two murders, you can imagine the way I feel about Bush.

Some people must have said, "Bugliosi's gone off the deep end on this one."

Jerry Brown called me: "I understand you have a book out about Bush, about impeachment," and I said, "No, Jerry, it's about murder."

My first challenge was to see if a president taking the nation to war on a lie fell within the conventional principles of criminal law, and I've come up with very solid evidence that it does. There are many sophisticated issues, but here's the main issue. I've established jurisdiction, federal and local. If a prosecutor could prove that Bush took this nation to war under false pretenses, then these killings of American soldiers in Iraq would become unlawful and therefore murder.

I get the feeling you wish reporters were coming to your door to talk about your Bush book instead of Manson.

Oh, absolutely. I would much prefer to talk about this, but people don't want to.

You have a theory about why the book didn't get much press.

I had a very difficult time getting this book published, and I've never had trouble getting a book published. I couldn't get on any networks, no cable. Everyone has been terrified to talk about this. My only master, my only mistress, is the facts. If a Democratic president had done this, I would have written the same identical book, so it has nothing to do with politics. I'm 95% sure the left in this country is terrified of the right. The right has no fear of the left -- the left is terrified of the right.

What do you think of televising trials?

We should not televise trials. There's only one purpose for a criminal trial. It's to determine whether or not the defendant committed the crime. Anything that interferes or has the potential of interfering with that should automatically be prohibited. The idea of education is nonsense. Televise an automobile-collision case or breach-of-contract case and see how many people watch. It's all about entertainmen

Good Reporter Dumb Article

By LINDA DEUTSCH (AP) – 13 hours ago

LOS ANGELES — Forty years ago, they were kids. Vulnerable, alienated, running away from a world wracked by war and rebellion. They turned to a cult leader for love and wound up tied to a web of unimaginable evil.

They were part of Charles Manson's "Family" and now, on the brink of old age, they are the haunted.

"I never have a day go by that I don't think about it, especially about the victims," says Barbara Hoyt who was 17 the summer of the Sharon Tate-LaBianca murders. "I've long ago accepted the fact it will never go away."

The ones who aren't in prison are scattered across the country. Some live under assumed names to hide their past from friends and business associates. Some have undergone surgery to remove the "X" that Manson ordered them to carve on their foreheads, showing they were "X"ed out of society. Some live with endless regret.

Those who escaped taking part in the spasm of terror that snuffed out at least nine lives would seem to be lucky. But their lives have been linked forever to one of the craziest mass murders in history.

"Manson made a lot of victims besides the ones he killed," said Catherine Share, who once lived with the Manson Family under the nickname "Gypsy." "He destroyed lives. There are people sitting in prison who wouldn't be there except for him. He took all of our lives."

It was 1969, the summer of the first moon landing. War was raging in Vietnam. Hippies were in the streets of San Francisco, the last bastion of the waning counterculture movement.

For many, that summer is remembered for one thing — the most shocking celebrity murders to ever hit Los Angeles. Mention of the Sharon Tate murders or the name Manson four decades later is enough to make people shudder.

On the morning of Aug. 9, a housekeeper ran screaming from a home in lush Benedict Canyon. She had discovered a scene of unspeakable carnage. Five bodies were scattered around the estate.

The most famous, actress Sharon Tate, 26, the pregnant wife of director Roman Polanski, had been stabbed multiple times. But there were four others that day and two more the next.

Abigail Folger, 25, heiress to a coffee fortune; Jay Sebring, 35, celebrity hair stylist; Voyteck Frykowski, 32, a Polish film director and Steven Parent, 18, friend of the caretaker, were found stabbed or shot in a bloody scene.

On the front door the victims' blood was used to scrawl the words, "Death to Pigs."

The city was thrown into a state of fear. If that was not enough, a similar murder scene was discovered the next night.

Wealthy grocer Leno La Bianca, 44, and his wife Rosemary, 38, were found stabbed to death in their home across town. A killer had carved the word "WAR" on Leno La Bianca's body. The words "Helter Skelter" were written in blood on the refrigerator.

"These murders were probably the most bizarre in the recorded annals of American crime," said Vincent Bugliosi, the former deputy district attorney who prosecuted the killers and wrote the book, "Helter Skelter."

It would be more than three months before the name Charles Manson was linked to the crimes. And then the story became even weirder.

The discovery of Manson's clan living in a high desert commune opened up the astounding story of an ex-convict who had gathered young people into a cult and ordered them to kill. His reasons still remain a subject of debate. Some say he wanted to foment a race war; others say it was senseless.

"It was a real-life horror story," recalled Stephen Kay, who also prosecuted the Manson Family. "Manson is the real-life Freddie Kruger."

The former prosecutors worry that Manson, 74, is becoming a folk hero to a new generation. He is the subject of several Web sites, and Manson souvenirs are sold online.

"Evil has its lure and Manson has become a metaphor for evil," said Bugliosi.

Those cult members lucky enough not to have killed for Manson on Aug. 9-10, 1969 have spent decades trying to bury their past and free themselves from his grasp.

Some never succeeded. Sandra Good and Lynette "Squeaky" Fromme committed crimes later that they said were for Manson and went to federal prison.

When Good, 65, was paroled she moved near the maximum security prison that holds Manson, reportedly so she could "feel his vibes." Fromme, 60, is due for parole this summer after serving 33 years for the attempted assassination of President Gerald Ford.

In 1969, there were perhaps 30 of them, a ragtag band of runaways and dropouts living on a movie ranch in the San Fernando Valley, all loyal to a shaggy-haired con man who preached a gospel of violence. Five of the "Family" members and Manson are in prison for the infamous Tate-LaBianca murders. Three are in prison for others crimes and two have been released.

Those who are free are still trying to sort out how they fell under his spell and how they came so close to one of the worst crimes of the 20th century. This is the anniversary of their nightmare.

They were very young when they found Manson — or he found them. Some were just 14. Others were in their late teens and early 20s.

Share muses how she might have been a lawyer or journalist had she never met Manson.

"We were just a bunch of kids looking for love and attention and a different way to live," recalls Share, 66. "He was everything to us. He was a con, a manipulator of the worst kind."

Hoyt was a 17-year-old who had left home after an argument with her father. She was sitting under a tree eating her lunch when a group of Manson followers came along in a van and asked her to go with them. They went to a house in the San Fernando Valley.

"I met Charlie the next morning," she said. "He took me for a motorcycle ride and we went for doughnuts. He was very nice. I thought he was pretty neat."

She said she was told by others of Manson's prediction of a race war that would destroy all but his followers who would go to the desert to live in a bottomless pit until it was safe for them to emerge and take over the world. She said she didn't believe much of it, but they were fixing up dune buggies for their escape and it was fun.

Hoyt and Share eluded being tapped for the Tate-LaBianca murders for different reasons.

"I was very young and I hadn't been there very long," said Hoyt. Others had joined the family long before she had and had been subject to Manson's "deprogramming," which included group sex and LSD trips.

"I wasn't as dead in the head as others. He asked me one time if I could kill and I said if someone asked me I would talk my way out of it. There were other people willing to do it."

Share said she was never asked, partly because she was older. But there was another reason: an extra 20 pounds that would have made it difficult for her to climb through windows.

"Let me tell you," she said, "I was just short of murdering for him. If he had told me to get some black clothes and get in a car, I would have."

The two women, who are not in touch with each other, have struggled back to normalcy. Share became pregnant while living at Spahn Ranch and has a grown son who served in the Marines. She declines to identify the father but said it was not Manson or any other notorious cult figure.

She went to prison for five years for involvement in a Manson Family robbery and later did more time for credit card fraud. She said the time in prison helped her recover and she became a Christian. Some of those in prison also have embraced Christianity.

Share went into retail sales and has just finished a book on her experiences with the Manson Family.

Hoyt went to college and became a nurse and is proud of her accomplishments.

"I raised my daughter; I have my own home and I've had some vacations," she said. But memories haunt her and she doesn't reveal where she's living.

"People freak out when they find out about my past," she said.

She keeps track of the Manson Family members in prison and writes letters urging that they never be released.

Share is more sympathetic to those who were convicted. Susan Atkins, 61, who is dying of brain cancer and had a leg amputated, has been turned down for compassionate release and has a parole hearing coming up in September. Leslie Van Houten, 59, and Patricia Krenwinkel, 61, convicted with her, remain in prison for life as does Charles "Tex" Watson, 63, another of the killers.

"Everyone wants to make them monsters," said Share. "They weren't monsters. They did a monstrous thing and now they're older people and they're not monsters anymore. None of those people ever would have been violent if it weren't for Manson."

More Superficial REegugitation

Manson Murders: 40 Years Ago

It was 40 years ago Sunday that America's worst fears of the hippie generation crystallized when Sharon Tate and four others were slaughtered by Charlie Manson's "family" in her rented Benedict Canyon home.

On Aug. 9, 1969, coffee heiress Abigail Folger, Voytek Frykowski, Jay Sebring, Steven Parent and Tate -- who was 26 years old, eight months pregnant and married to film director Roman Polanski -- were slain "to instill fear into the establishment," one of the killers, Susan Atkins, later told a grand jury.

A day later, Manson's followers struck again -- slashing to death grocery store chain owner Leno LaBianca and his wife, Rosemary, in their Los Feliz-area home.

The murderers left bloody messages at both crime scenes, including the title of a Beatles song, "Helter Skelter," in what authorities believe was an effort to start a race war.

Shocking Celebrity Deaths: Tate Murdered 40 Years Ago

Manson's brief reign of terror is four decades ago, but it continues to have a hold on America's psyche.

Sandi Gibbons covered their trial for City News Service. Today, she is a spokeswoman for the Los Angeles County District Attorney's Office, which prosecuted the case.

What Charlie Manson meant to America was "the death of the hippie movement," Gibbons told CNS.

The Manson family was "the dark side of the peace, love and brotherhood movement," she said. "These were still the '60s, with flower children, love-ins ... peace-loving druggies ... but Manson was another side altogether. This was murder. This was killing people."

She said that from the moment Manson's family was uncovered at their commune in Death Valley a couple months after the murders, "people looked at hippies in a different light."

She added that the commune movement also "started shrinking."

But Gibbons said she never considered Manson a hippie. Rather, she said, he was simply a "con man."

She said he knew "how to get people to do his bidding through drugs, spouting a bunch of philosophy to a bunch of drugged-out kids, promising them a home -- sex, drugs and rock 'n' roll. The main thing was that Charlie was never a hippie."

She noted he had been institutionalized for most of his life since he was a child and that he discovered the hippies in the late '60s after he got out of prison in Washington state and "wandered down the coast to the Haight Ashbury District of San Francisco."

She said he played the guitar and gathered a small following, and that "his visions didn't turn dark until he got rejected in Los Angeles on the music front."

"The bottom line is that Charlie was a con man, and he's still conning people," she said. "I was raised in the South, and Charlie to me was a redneck Southerner who did not like women -- they were something to use, and he used them well."

Manson has repeatedly been turned down for parole, as have the so-called Manson women, even when one of them became terminally ill with brain cancer.

When asked for her personal opinion on whether the women should be paroled after 40 years, Gibbons said that as a spokeswoman for the District Attorney's office she couldn't discuss that.

"So far, this office has opposed parole," she said.

Gibbons noted the Manson women were in their mid 20s when they committed their crimes, and that she wasn't much older at the time.

"I could easily have been them -- but I wasn't," she said.

She said she sat behind Manson during some of the trial, and did not consider him to be charismatic in the least.

"He was like 5 feet 2 inches, a little redneck Southerner. I did not find him charismatic, or fascinating or interesting. He was a little creep."

Sadie Claimed She would be long dead by now

Susan Atkins On Quest For Parole, Forty Years After Charles Manson Murders

The Convicted Killer Is Very Ill and Faces a Hearing in September

By JIM AVILA and FELICIA PATINKIN

Aug. 7, 2009—

These days, it is difficult to recognize the face of Susan Atkins, a notorious murderer from the Charles Manson cult. Still imprisoned, she's now gravely ill with brain cancer and asking for mercy that she did not give her victims.

Forty years ago, Atkins, 61, was a member of Charles Manson's "family," and took part in one of the most evil crimes in American history.

It was Atkins who held down pregnant actress Sharon Tate while she was stabbed 16 times.

Atkins described the crime in blood-curdling detail at a parole hearing 16 years ago.

"She asked me to let her baby live," Atkins said at the time. " I told her I didn't have mercy for her."

Manson ordered Atkins and other "family" members to kill eight people, including Tate and wealthy store owners Leno and Rosemary La Bianca, in the Los Angeles area in August 1969.

Manson masterminded the murders hoping to start a war between blacks and whites, which he believed was foretold in the Beatles' song "Helter Skelter."

In the months after the bloody spree, Manson and his "family" were swept up. Atkins initially agreed to cooperate with prosecutors to avoid the death penalty, but soon she stopped cooperating. Instead, she and other women loyal to Manson disrupted court proceedings and sang songs written by Manson on their way to court. Atkins later testified that Manson was not involved in the Tate murders. For the crimes, Atkins was sentenced to death along with Manson and three others. When the Supreme Court struck down all death sentences in 1972, Atkins' sentence was automatically commuted to seven years to life with the possibility of parole, the maximum sentence at the time.

In prison, Atkins claimed to be a born again Christian and in 1980 married Donald Lee Laisure who claimed to be wealthy and would work to get her out of prison. She divorced Laisure soon after, and married James Whitehouse, a lawyer who has been devoted to Atkins ever since and has argued for her release.

Should Susan Atkins Be Released?

Today her family argues that Atkins is so ill that she can no longer pose a threat to society.

With the California budget in meltdown, they argue that Atkins should be released. They contend that it would save the state up to $10,000 a day when she's hospitalized. For example, last year alone she spent six months in an intensive care unit at the state's expense.

"She's paralyzed just about 85 percent of her body. She can nod her head and she can look left and right and she has limited use of her left arm," said her husband, who drives 1,000 miles a week to see her.

Now virtually alone and dependent on her devoted husband, Atkins is asking that her life sentence be cut short so she can die at home, rather than in the California prison system where she has been for 39 years. She has been denied parole repeatedly, despite expressions of regret to her victims and their loved ones.

"She's expressed her remorse and grief at every single one of her 17 other parole hearings going back to 1972," says Whitehouse.

In 2002, "Good Morning America's" Diane Sawyer met Atkins in prison while she was working with other women who had life sentences.

She said she was a changed woman.

"I am not the same person that I was when I came in here," she told Sawyer at the time. When asked if she expected to be released from prison, Atkins replied, "I would like to be out some day."

Still clinging to that hope, Atkins and her family will again appear before a parole board this September to make their plea official.

But the Manson victims' families and their advocates dismiss economics as a good reason for early release.

"The very release of a killer like that & sends a message to people that this life sentence doesn't mean a life sentence, that the victims' families are going to have to go through this over and over and over again," said Jennifer Bishop-Jenkins, an advocate for the victims. "She needs to, in grace and dignity, finish her sentence."

Let's Claim Charlie was a Hippie

Toronto Star

There's no use going looking for 10050 Cielo Dr. any more. It's gone, razed more than a decade ago. On the rough, tumbling northern slope of the San Fernando Valley's western edge, north of Beverly Hills, the house that stands there now shows a different address.

But that hasn't stopped legions of gawkers from rubbernecking their way up the scrubby valley wall along Cielo Dr., spectrally still and remote. It is a macabre pilgrimage, to the place where, 40 years ago tomorrow, a generation's defining criminal atrocity took place.

Four decades later, the multiple murders of actress Sharon Tate, eight months pregnant at the time; her former fiancé, hairstylist Jay Sebring; Voytek Frykowski, a friend of Tate's husband, director Roman Polanski; and Abigail Folger, the Folger's Coffee heiress, still resonate with a grim, consuming clarity.

Feel-good nostalgia tells us that 1969 was the height of the hippie, warm-fuzzy era of peace and love, and that this week's other 40th anniversary, of the Woodstock music festival, was its pinnacle: A moment where individualism, non-conformity and the creative impulse reigned, where repression was challenged and, in many ways, fell.

But that's rose-coloured hindsight of a fractious time that unleashed demons as much as it seeded naïve idealism. The Cielo Dr. killings, and the murders of Leno and Rosemary LaBianca in Los Feliz a day later, were as much a product of those times. No one embodies this dark flowering more than the murderers' puppetmaster, Charles Manson. And his stamp on the culture is arguably deeper and more lasting than Woodstock's.

Part of it, surely, is the extremeness of the violence, executed with a cool sense of purpose – 102 stab wounds inflicted on the four victims in the house plus Steven Parent, an 18-year-old delivery boy shot dead in the driveway on his way home as the killers made their way to the house.

The next night, the killing continued, this time in the hills of Los Feliz, where Leon and Rosemary LaBianca were murdered in much the same way, stabbed with a knife and fork. Leon's stomach had carved on it the word "WAR."

But just as horrifying as the brutal nature of the crimes were the killers themselves: Tex Watson, Patricia Krenwinkel and Susan Atkins – long-haired flower children, and proverbial "good kids," for the most part; Watson was an A student and high-school star athlete; Krenwinkel the daughter of an insurance executive and an actual choirgirl.

But Manson, their patriarch and orchestrator of the murders, looms huge over them all, and the entire counterculture generation.

The killings were a perplexing infusion of revulsion in what was, by now, a waning countercultural movement: The Manson "family," as they called themselves, were hippies, for all appearances – charter members of the peace and love generation, which met violence with sit-ins, and guns with flowers. They were political and anti-establishment, as were so many of their generation. They were indulgent users of drugs like marijuana and LSD. They lived on a commune, the Spahn Ranch, and were, by many eyewitness accounts, practitioners of "free love."

But when their time came in court, the world was shocked to see the women, in hippie garb, holding hands and singing, ridiculing prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi, laughing at his accounts of their crimes.

"The mantra of the era was `peace, love and sharing,'" says Bugliosi. "Prior to (the Manson case), people just didn't identify hippies with violence. Then the Manson family comes along, looking like hippies, but being mass murderers. And that shocked America: How could this be?"

Trying to derive meaning from seemingly random acts orchestrated by a pyschopath is dangerous territory. But there's little question that the murders, both at the time and in hindsight, cast a pall over the counterculture. Violence in America was nothing new; neither was murder, nor were high-profile cases. But brutal, unjustifiable violence from within, committed in its name? This was something new.

A week after the murders, Woodstock took place in upstate New York, swelling spontaneously to a half-million kids listening to acts like Country Joe and the Fish, Santana and Jimi Hendrix. But it was revelry cast in dark shadow.

"The first thing to recognize is that the past and history are different," says John Storey, a cultural historian in the U.K. and the author of Cultural Theory and Popular Culture. "The struggle over the meaning of the '60s, for example, changes on whether we highlight Woodstock or Manson. This, in simplified form, could be said to be the difference between those who view the '60s and its legacy as positive or negative."

Meanwhile, the counterculture – to the conservative establishment at the time, not much more threatening than a bunch of lazy, misguided kids who needed to grow up – was morphing quickly from social revolution into fashion trend and marketing opportunity.

Earlier festivals, like The Human Be-In in San Francisco in 1967, were free; later that year, the Monterey Pop Festival was intended to raise money for free clinics (though the $500,000 it raised mysteriously disappeared).

By Woodstock, the naive sheen had dulled. "The real thing Woodstock accomplished," Bill Graham, the former manager of Jefferson Airplane, told Storey, "was that it told people rock was big business."

If Woodstock was the beginning of the end, then the murder indictments on Dec. 8, 1969, of Manson, Watson, Atkins, Krenwinkel and two other family members, Linda Kasabian and Leslie Van Houten, were to many its grim, undeniable conclusion.

"Is Charles Manson a hippie?" asked Rolling Stone in one cover story. "The '60s abruptly ended on August 9, 1969," the date of the murders on Cielo Dr., wrote Joan Didion in her 1979 collection of personal essays on life in the '60s, The White Album.

That was a philosophical take. At the time, others were more practical, driven by fear. In the October 1969 issue of Los Angeles magazine, spurred by the Manson family murders, Myron Roberts wrote an alarmist indictment of a generation run wild, fuelled by drugs, lax morals and a loss of standards.

He chided Life magazine's special edition on Woodstock for making it "a cultural event of monumental import, just behind Genesis and landing on the moon." Woodstock was lauded for being civil, to which Roberts wrote that "no one stopped to ask why the absence of violence at a large, public gathering of the young should be considered more remarkable than the fact that the fans who go to football games ... do not customarily tear up the stadium or attack one another."

He then compared Woodstock to "another youth festival – the Nuremberg Rallies – where Hitler, Goebbels & Co. were the featured group and the multitudes of fans were stoned on slogans, not grass." Not finished yet, he concluded the article with a practical guide to "protecting yourself from `freaky' crime" – meaning drug-induced, of course, perpetuated by a darkening culture of hippiedom.

And this was before any of the Manson crew had been caught. When Manson, looking beatific, long hair and beard flowing, was arrested, the dark side of the era had a face. And when the grisly details of the murders came out, the death knell for the counterculture was sounding loud and clear.

It is, by now, a gruesome litany: Manson was obsessed with the Beatles, who were central to the countercultural movement. The White Album in particular. He believed they were sending him messages, enlisting him to start a revolution. The song "Helter Skelter" became, for him, a command to start a race war between blacks and whites; "Piggies," ridiculing the British upper classes eating "with forks and knives," was for Manson an invitation to wipe out the wealthy ("what they need's a damn good whacking," the song went).

The Tate house was chosen over an old grudge that had nothing to do with Tate or any of the other victims. Manson, an aspiring songwriter, had auditioned there for producer Terry Melcher when he lived there with his then-girlfriend, Candice Bergen. Melcher, after witnessing Manson in a frenzied fight one night, broke off ties, which infuriated Manson.

The night of the murders, when the family members arrived, Parent was rolling down the driveway. Watson shot him dead at the wheel. He then cut the phone line, and the three made for the house.

Slitting a screen, the threesome slipped inside. Tate, Sebring and Folger, thinking they were being robbed, were tied by the neck with a rope, which was flung over a support beam in the living room. They asked what would happen to them. "You're all going to die," Watson said calmly. Panic took hold.

Frykowski got loose and burst outside, screaming for help. Watson stabbed him 51 times. Inside, Tate, Sebring and Folger struggled to get free. The stabbing, 102 wounds altogether, came in a flurry. Tate, who was eight months pregnant, begged to be allowed to have her baby. Atkins stabbed her 16 times. In custody, she told Bugliosi that she told Tate, before she killed her: "Bitch, you're going to die. I don't have any mercy on you." When she was done, she wrote "PIG" in Tate's blood, before taking a shower and leaving the scene.

The next night, the Manson family, this time joined by Kasabian, Van Houten and Manson himself, went looking for more victims. They chose the LaBianca house at random.

"If you were white and appeared financially well-off, you qualified to be murdered," Bugliosi said. The killers used knives and forks – an apparent reference to the Beatles song – and left the LaBiancas butchered in their home, but not before raiding their refrigerator and showering.The fallout was severe. Once the Manson family was revealed, the establishment's dim view of counterculture turned rabid and extreme. Even Polanski himself was implicated.

"In their rush to assess what had happened, some of the mainstream press brought the nature of Roman Polanski's movies into the nature of the crime and held (his) movies responsible," Warren Beatty told Los Angeles magazine recently. "Roman was a total innocent. Neither his life nor his movies had anything to do with this. But because he'd made Repulsion and Rosemary's Baby he was made to seem responsible."

For some, the counterculture was already teetering under the weight of its own portent. Indulgent and hedonistic, it had become bloated and without focus – a set of superficial trends, not a social revolution. The Manson crimes represented a shocking extreme to a culture that was becoming increasingly incoherent.

"What struck me about the Manson murders was how at the moment they happened, it seemed as if they were inevitable," Didion said, during an interview at the National Book Awards. "It seemed as if we had been moving toward that moment for about a year."

Bugliosi had no such sense at the time. "I'm not a sociologist. I was just trying one murder case after another," he says. "But looking back, it seems to be the consensus of many that the Manson case sounded a death knell for hippies and everything they symbolically represented."

High above the San Fernando Valley, on Cielo Dr., the quiet absence of No. 10050 says much the same thing.

Wednesday, August 05, 2009

Squeaky Gonna Move Next Door to YOU

After 34 years, Lynette 'Squeaky' Fromme to be released

- Story Highlights

- "Squeaky" Fromme was convicted in 1975 of pointing a gun at then-President Ford

- For years, she was one of Charles Manson's few remaining followers

- According to reports, she for years waived her right to a parole hearing

- She was not involved in the murders that landed Manson, other followers in prison

CNN

(CNN) -- The president she once pointed a gun at has been dead for nearly three years, and her longtime idol and leader, Charles Manson, remains in prison.

However, Lynette "Squeaky" Fromme is about to get her first taste of real freedom in more than three decades.

According to the Federal Bureau of Prisons, Fromme, now 60, is set to be released on parole August 16.

Fromme is housed at the Federal Medical Center at Carswell, Texas.

For years, she was one of Manson's few remaining followers, as many other "Manson Family" members have shunned him. A prison spokeswoman would not say whether Fromme continues to correspond with Manson.

Fromme was convicted in 1975 of pointing a gun at then-President Gerald Ford in Sacramento, California. Secret Service agents prevented her from firing, but the gun was later found to have no bullet in the chamber, although it contained a clip of ammunition.

In a 1987 interview with CNN affiliate WCHS, Fromme, then housed in West Virginia, recalled the president "had his hands out and was waving ... and he looked like cardboard to me. But at the same time, I had ejected the bullet in my apartment and I used the gun as it was."

She said she knew Ford was in town and near her, "and I said, 'I gotta go and talk to him,' and then I thought, 'That's foolish. He's not going to stop and talk to you.' People have already shown you can lay blood in front of them and they're not, you know, they don't think anything of it. I said, 'Maybe I'll take the gun,' and I thought, 'I have to do this. This is the time.' "

She said it never occurred to her that she could wind up in prison. Asked whether she had any regrets, Fromme said, "No. No, I don't. I feel it was fate." However, she said she thought that her incarceration was "unnecessary" and that she couldn't see herself repeating her offense.

"My argument to the jury was, if she wanted to kill him, she would have shot him," John Virga, a Sacramento attorney appointed to defend Fromme, told CNN on Tuesday. "She'd been around guns. And let's be realistic: We know the Manson family, at least some of them, are killers."

Fromme was sentenced to life in prison, but parole was an option at the time, although the federal system later abolished it, said Felicia Ponce, spokeswoman for the Bureau of Prisons. Inmates do receive "good time" -- for every year and one day they serve, Ponce said, 54 days are lopped off their sentence.

Fromme became eligible for parole in 1985, Ponce said. According to reports, she for years waived her right to a parole hearing. The Bureau of Prisons would not say whether she changed her mind and requested a hearing, but the U.S. Parole Commission's Web site says that everyone who wishes to be considered for parole, except those committed under juvenile delinquency procedures, must complete a parole application.

Federal inmates serving life are generally paroled after 30 years, unless the parole commission decides to block the release, according to a commission spokesman. Inmates who are paroled remain under supervision until the commission decides to terminate the sentence.

Fromme was not granted parole until July 2008, Ponce said. She was not released then, however, because of extra time added to her sentence for a 1987 escape from the West Virginia prison, which occurred after her interview that same year. She was found two days later, only a few miles from the prison. At the time, prison officials said they were looking into rumors that Fromme escaped after hearing Manson was ill, according to news reports.

FMC-Carswell spokeswoman Maria Douglas would not comment on Fromme's behavior in prison in recent years.

Fromme reportedly joined Manson's family after meeting him in California in 1967. She was not involved in the murders of seven people, including pregnant actress Sharon Tate, on August 9 and 10, 1969, that landed Manson and other followers in prison. However, she and other Manson followers maintained a vigil outside the courthouse during his trial.

In the WCHS interview, Fromme said that Manson should not be incarcerated because "he didn't kill anybody. ... I would rather be in, because I know I laid a lot of my thinking in his mind."

Virga said he told the jury that Fromme assaulted Ford, but did not attempt to assassinate him. If Fromme had killed the president, no one would have listened to her, he said. "She didn't want people to think she was a kook."

And she wasn't, he said, recalling that Fromme was very cooperative during her trial and describing her as "a bright, intelligent young woman" from a middle-class family. "It's just hard to imagine how she got all caught up with Manson," he said.

Fromme wanted to be heard on issues including the environment, he said. "She had certain causes that she wanted to talk about. But first and foremost in her mind was always Manson."

Explaining herself after the attempt, according to the book "Real Life at the White House," Fromme said, "Well, you know, when people treat you like a child and pay no attention to the things you say, you have to do something."

During her trial, Virga traveled to Washington to depose Ford, who testified on videotape about the incident.

In the 1978 interview, Fromme called Manson "a once-in-a-lifetime soul. ... He's got more heart and spirit than anyone I've ever met." She said she still corresponded with him. "He's got everything he wants coming from me, 'cause he gave me everything."

She said then she didn't plan to seek a parole hearing: "The parole board does not hold my life in its hands. And I don't want to be too critical, but men tend to think they do. Charlie never thought he did. He never expressed all this desire for power, this desire for acceptance."

Ford died in 2006 at age 93. The Gerald R. Ford Presidential Foundation did not respond to CNN requests for comment on Fromme's release.

Virga, who is still practicing in Sacramento, said he had not heard from Fromme since her sentencing in 1975. "I wish her the best, and hope everything works out for her, and hope she stays out of trouble," he said. "She needs to stay out of trouble. She's been in prison a long time ... it was, in my mind, a tragedy that she wound up a disciple of Manson."

Monday, August 03, 2009

Questions for the Bug

So this radio station is interviewing Bug. Click here.

It will probably be the same old shit. In the remote chance they have testes, we have sent in these questions to be asked.

1- Why do you still put forward your theory of Helter Skelter as the main motive for the killings? Your predecessor Aaron Stovitz has publicly called it bullshit, the killers themselves have dismissed it yet you persist in this fairy tale. Why?

2- Do you still worry that Herbert Weisel might be the father of your eldest son?

3- Why is it that after 40 years you still show up on almost any program involving Manson? Is this your primary legacy?

4- Whatever happened to Virginia Cardwell, the mistress that you beat up when she lied to you about getting an abortion in 1973

Bug Jabbers in NewsWeek

The Manson Murders at 40

NEWSWEEK

Published Aug 1, 2009

From the magazine issue dated Aug 17, 2009

The leaves were turning on the summer of love. Vietnam was droning on. Racial unrest was rising. And then, it happened: a crime so heinous, it sent shock waves through the country that are still palpable today. The Manson "family" murders are more than grisly crimes. They marked the close of an era. As Joan Didion wrote in her memoir of the time, The White Album, the '60s "ended abruptly on August 9, 1969," the evening Sharon Tate and four others were brutally slaughtered in cold blood, a night before another round of senseless killing claimed two more lives. >Vincent Bugliosi, the chief prosecutor in the case, secured first-degree murder convictions against Manson and his codefendants; the jury returned verdicts of death, which were subsequently reduced to life imprisonment when California set aside the death penalty in 1972. Bugliosi went on to co-author a book about the case with Curt Gentry titled Helter Skelter (after the Beatles song name printed in blood at one of the murder scenes), which became, according to his publisher, the bestselling true-crime book of all time. Bugliosi spoke with NEWSWEEK's Tom Watson on the eve of the 40th anniversary of the Manson murders about what it was like to prosecute the case, and why Manson's chaotic charisma continues to attract global attention to this day.

Watson: Set the scene for us. What was the mood of the country, and of Los Angeles, on the eve of the Manson murders?

Bugliosi: I can't speak for the rest of the country, but I can tell you that in L.A., it was a time of relative innocence. I've heard many people say that prior to these murders, there were areas of the city where folks literally did not lock their doors at night. That ended with the Tate-LaBianca murders. The killings were so terribly brutal and savage: 169 stab wounds, seven gunshot wounds. They appeared to be random, with no discernible conventional motive. That induced a lot of fear throughout the city of Los Angeles, particularly in Bel Air and Beverly Hills, the heart of the movie colony, where the Tate murders happened (the LaBianca murders happened across town, near Griffith Park). Names were dropped from guest lists. Parties were canceled. No one knew if the killers were among them. Overnight, the sale of guns and guard dogs rose dramatically.

Why did the crimes penetrate so deeply in the American psyche? How did the culture change in the immediate aftermath?

I was just involved prosecuting one murder case after another, so I'm not someone who's a sociologist. But the killings tapped a feeling of dread … if you're not safe in your own home, where are you safe? And the very thought of young women dressed in black, armed with sharp knives, entering the homes of complete strangers in the middle of the night and mercilessly stabbing them to death … it's difficult to even contemplate a thought like that.

The other thing that terrified the nation so much is when the identity of the killers became known. And who were they? Young kids from average American homes with fairly good backgrounds. There was a feeling that this could be our own children. Tex Watson, Manson's "chief lieutenant" at the murder scene, was from Farmersville, Texas, hometown of World War II hero Audie Murphy. Watson was a football, basketball, and track star. He had almost an A average in high school. And when the people in Farmersville learned he was being charged with these murders, the general consensus was this is absolutely impossible, it must be a case of mistaken identity. Patricia Krenwinkel—another one of the main killers—her father was an insurance executive; she sang in the church choir; got good grades in school; at one time she even wanted to attend a Jesuit college in Alabama. Leslie Van Houten—another killer—she was a homecoming princess at Monrovia High School here in L.A.

How did Manson seduce these kids?

Manson is this 5-foot-2 guru with a long and checkered criminal history. He gets out of Terminal Island federal penitentiary off Long Beach, Calif., in 1967, goes up to the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco. He's got his guitar, and his street rap, and he sings—a pretty good composer of music, by the way. Guns N' Roses and the Beach Boys have recorded Manson songs. So he mesmerizes these young kids and tells them things they can identify with—about the need for the preservation of wildlife, that there's pollution of the environment by big corporations, that the poor man's fighting the rich man's war in Vietnam …. Their lifestyle was sex orgies and LSD trips. He convinces them he's the second coming of Christ and the devil all wrapped up into one person, and ultimately, as you know, he gets them to kill for him. He tells them the purpose for these murders is to start a war between blacks and whites, which he called Helter Skelter, after the Beatles song.

Fast-forward to the trial. What was the atmosphere at the courthouse, and the most dramatic moments in prosecuting the case?

It was the longest murder trial we'd ever had in America up to that point: nine months. And it was the most expensive up to that point, at $1 million. Outside the courthouse, there was a group of Manson family members conducting a 24-hour-a-day vigil for him. The media was interviewing them every day. Manson came into court one day with an X carved into his forehead, and the next day they all had X's on their foreheads. One day during the trial, he got ahold of a sharp pencil, and from a standing position, he leaps over the counsel's table with this pencil and starts approaching the judge. The bailiffs immediately tackled him and, as they were dragging him out of the courtroom, he shouted to the judge: "In the name of Christian justice, someone should chop off your head." The judge started carrying a .38-caliber revolver under his robe in court after that.

Even President Nixon got into the act. He was in Denver at a law-enforcement convention. He gives his opinion that he thought Manson was guilty. Ronald Ziegler, his press secretary, tried afterward to correct that, saying that the president meant to say allegedly guilty. But it had gone out over the wires. The main headline in the Los Angeles Times: MANSON GUILTY, NIXON DECLARES. Manson got ahold of that paper—no one knows how—stands up in front of the jury with a little silly grin on his face, and shows the jury the headline. It was almost as if he was somehow proud the president had taken notice.

Then near the end of the trial, a defense attorney vanishes from the face of the earth. Ronald Hughes was the defense attorney for codefendant Leslie Van Houten. The judge said, "Well, we're going to have to be in recess." Every morning we were hoping that poor Hughes would walk through the courtroom door, but he never did. So the judge had to appoint a substitute lawyer to take his place. On the last day of the trial, Hughes's body was found out in the forest, but the Ventura County coroner's office was unable to determine the cause of death because of the decomposition … I can't say positively one way or the other, but my leaning is that Hughes was murdered by the Manson family.

Give us an example of how widespread the interest in the case has been over the years.

Let me tell you a story. Years ago, I spoke at a book convention in Richmond, Va. I arrived at the station at the same time as William Manchester and Arthur Schlesinger, both Pulitzer Prize winners. The whole cab ride, Manchester and Schlesinger are tossing me questions about Charles Manson. That's all they wanted to talk about: tell me about him. Tell me about his eyes. Did you ever talk to him? How did he get control over these people?

Have you talked with Manson since the trial?

No. He wrote me four letters. I didn't respond to any of them; I turned them over to the Department of Corrections... The latest one could have been 20 years ago. [Bugliosi declined to discuss the letters' contents.]

Leslie Van Houten comes up for parole soon. Have you ever gone to a hearing for one of the family members?

No. If it came down to a point where they were seriously considering releasing, let's say, Manson or Watson, I would intervene—not that I have any clout at all. But I would write to the governor. But it's not going to happen.

Place Manson in the pantheon of American criminal outlaws.

Most mass murderers have turned out to be of rather low intellect—drifters, loners. Basically, they committed the murders for one reason only: to satisfy their own homicidal tendencies. Manson not only is very bright—but as misdirected as his violence was, his murders were revolutionary, political, and therein lies his main appeal to those on the fringes. The other thing that has separated him is the fact that all these other mass murderers committed the murders by themselves. Manson, on the other hand, was pulling strings and getting people to go out and kill strangers at his command without asking any questions. And that makes him more frightening to people.

And people are frightened of his impact still.

Let me just read to you a letter I received from the BBC in 1994. This reporter wrote to me about many British and German rock bands playing Manson songs and songs in support of him. "For some reason the neo-Manson cult seems to center in Manchester, where there are five stores selling "Free Charles Manson" t-shirts, which are fantastically popular on rave dance floors, and bootleg records of his music …. The majority of the supporters of these bands are under 25. The truly frightening part is that many, when asked, turned out to be Manson buffs who have read all they can find about Manson, and strongly approve of 'Helter Skelter.' That was 15 years ago, but Manson is still big.

Find this article at http://www.newsweek.com/id/209940